Blood, Sweat and Cheer is an absurd high school comedy, directed by Traci Hays, that dances the line between drama and tragedy, sane and insane. Ostensibly about the frayed relationship between a mother and a daughter, the film unravels along with its central protagonist with mixed success. Ultimately, the film’s tonal inconsistencies win out, something that echoes through the muddled writing and performances. This being said, the film is not without merit. The costume and set design feels sufficiently distinctive, while clearly borrowing from films such as Heathers, But I’m A Cheerleader and Clueless. The contemporary soundtrack also works to good effect, helping to provide necessary speed to some of the action.

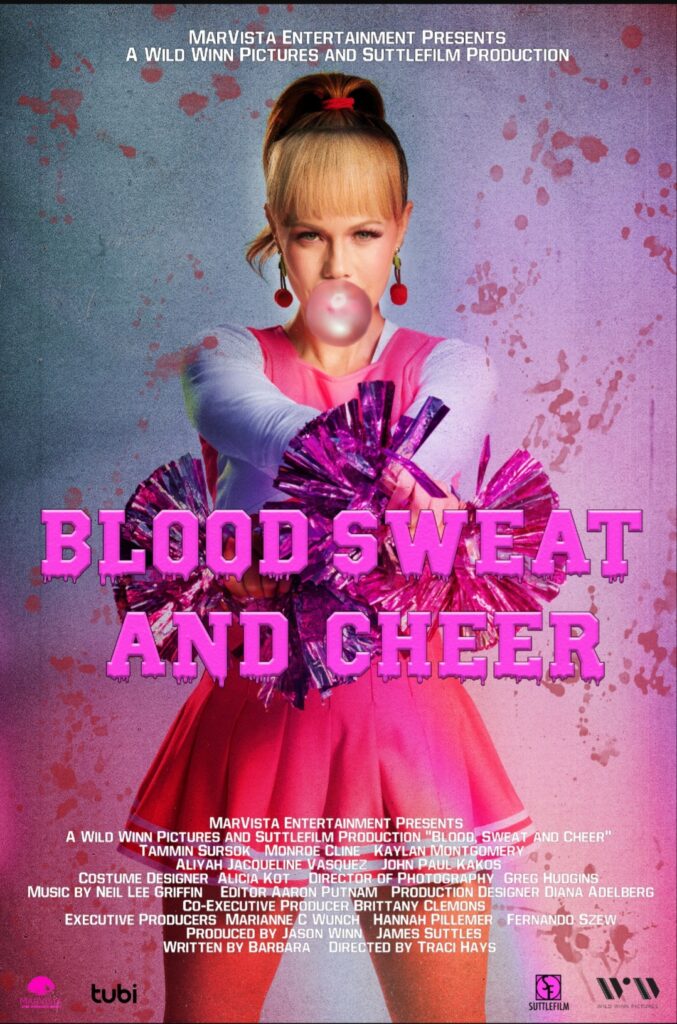

A short opening prelude sets the tone for the film: the camera moves across a cabinet of trophies, three girls stride in slow-motion, the hallway turning into a makeshift catwalk. The girls own the space, while an energetic and powerful track plays in the background. As one of the girls approaches the top of the stairs, a hooded person suddenly appears and pushes her back down—she tumbles and tumbles. The hooded person, as we will find out, is Renee (Tammin Sursok). Renee chews her bubble gum and it pops—the opening titles for Blood, Sweat and Cheer appear on screen. Immediately we are exposed to the playfulness of the film, the tongue-in-cheek rivalries and hierarchies, as well as a hint of something more sinister lurking under the surface.

In the first part of the film, Cherie (Monroe Cline), Renee’s daughter, desperately tries to disentangle herself from her mom’s overbearing helicopter parenting. She decides to quit the cheer team, transfer schools and move in with her dad (Collin Shephard)—abandoning her mom and a chance at a scholarship. Having confiscated Cherie’s phone in the process of her leaving, Renee answers a call pretending to be her daughter. It’s from Coach Forrest (Sasha Hatfield) at Mountain Valley: she is offering a college cheerleading scholarship. Renee’s plan begins to form, a plan that develops when Hayden (Anna Rappaport), one of the other cheerleaders, mistakes her for Cherie at practice. At home, standing in front of the mirror, Renee transforms herself, now wearing pigtails and pink, and imitates her daughter’s mannerisms. Determined to win the cheerleading scholarship, Renee enrolls at Lincoln Public High School masquerading as Cherie. What could possibly go wrong, or rather what could possibly go right?

Blood, Sweat and Cheer certainly stretches the limits of suspension of disbelief, perhaps even to the point of snapping. The film works on the basis that you assume the likeness of Renee and Cherie, which isn’t a problem—lots of films operate this way. The greater problems arise when the plot develops. The way events are contrived, and the way characters interact, makes it increasingly difficult to maintain blind hilarity towards it. The film seems to be aware of the real world consequences of Renee’s actions, even writing them into the story, but then chooses to ignore them in the subsequent scenes. Moments of genuine condemnation are followed by more or less the same behaviors played for laughs. The tone is confused as the film desperately clings to its comedic elements, this despite depicting increasingly problematic situations. If the film committed to a full descent into delusion, peeling back artificial layers, mirrors invading from all directions, the light and color draining from the costume and set design, a more satisfying and impactful conclusion might have been reached.

Though written too plainly on the surface, with almost no subtext, the film does deal with a serious delusion: that of parents living vicariously through their children while, at the same time, blaming them for the loss of their own dreams and aspirations. Renee never went to college because she had Cherie; she never got her cheerleading scholarship; she never became a professional dancer. You get the sense, especially as the film progresses, that Renee believed she was destined for stardom, however small that stardom might have been. Tammin Sursok, in the central role, is believable in this aspect—she plays the emotion well, if a little unanchored.

At least thematically, then, there are similarities to Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder and, more recently, Pearl by Ti West: the fallen youth in the first and the artistic delusion in the second. As Renee imitates her daughter’s voicemails, copies her reactions and impersonates her texting style, it is impossible not to feel at least a small sympathy for the insecure mother depicted on screen. The film does lose its proportions in the second half as Renee does more and more incomprehensible things, though the initial tension—between mother and child, past and future—is interesting enough.

The camerawork by Greg Hudgins is fundamentally sound without ever reinventing the wheel. In particular, the dance sequences are captured well which, combined with the soundtrack (by Neil Lee Griffin), adds a well-constructed kineticism to the film at important moments. Considering the chaos happening on screen at times, the cinematography does well not to add another layer of disorientation—it is often simple and restrained. The use of slow motion is at times superfluous, but at other times it blends well with the visuals and creates moments of intrigue. There is also a strong use of mirrors, which services the story and puts an exclamation point on some of the best scenes in the film.

Blood, Sweat and Cheer partly succeeds in creating a bizarre genre-straddling high school melodrama. It is calamitous and sprawling, and the film’s energy is noteworthy: it rattles through a significant amount of action in a relatively short run-time. Sursok’s central performance fills the space and she displays fragments of impressive emotional depth. Nevertheless, the film is let down by its written dialogue and plot development, which strains to link one event to the next. The absurdity of the film, not a problem in isolation, is undercut by interjections of real-world commentary in the mouths of the characters—leaving the tone caught between comedy and plain concern.