In exploring the enormity of life and its many possibilities, filmmakers often choose to focus on the younger generation. The brash, the brilliant, and those who haven’t quite figured out how they can situate themselves. However, the choice to feature the older generation in such stories has yielded some rather touching results over the past few years. Harry Macqueen’s Supernova and Florian Zeller’s The Father immediately come to mind, and director Stephen Gallacher’s Harold & Mary more than measures up to these titles with its gut-wrenching portrait of dementia.

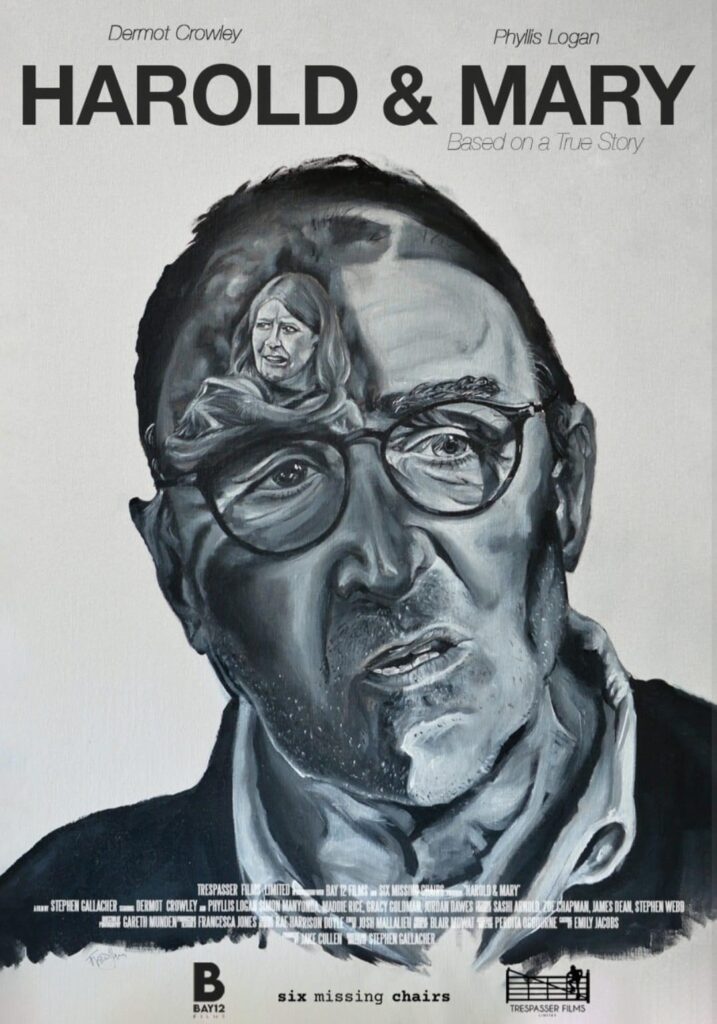

The 50th anniversary marriage celebrations of Harold (Dermot Crowley) and Mary (Phyllis Logan) prove to be short-lived, as Harold’s rapidly deteriorating mental state makes it impossible for him to remain in the couple’s home. His immediate family now faces a difficult predicament and is making arrangements to move him into assisted living as a last resort.

The film doesn’t shy away from showing just how fragmented Harold has become since his diagnosis. His ordeal is made even more tragic as neither of his loved ones can do anything to prevent his condition from worsening. It’s a losing battle—one Harold was never meant to win in the first place. This struggle is something that’s very well illustrated, with cinematographer Gareth Munden capturing it all in earnest. Blair Mowat also deserves praise for the score, along with the production design by Francesca Jones.

Crowley is extraordinary as Harold, lending grace to a character whose perception of reality has long slipped away. Logan is just as exceptional, with Mary sitting on the fringes, watching her husband gradually fall apart. It’s three worlds collapsing at once, the third being the one they once shared years ago. Gallacher’s screenplay drops bits and pieces of the pair’s past relationship, one that is painted as a beautiful, rapidly fading memory.

While there is much heartbreak to go around, Gallacher finds a silver lining. Harold’s family still cares for him, and Mary is left with fond memories to reminisce about in her quieter moments. The inevitability of it all doesn’t come crashing down in a frenzy. This is twelve minutes of controlled, measured filmmaking at work. One that examines dementia in a familiar, but no less, devastating manner.