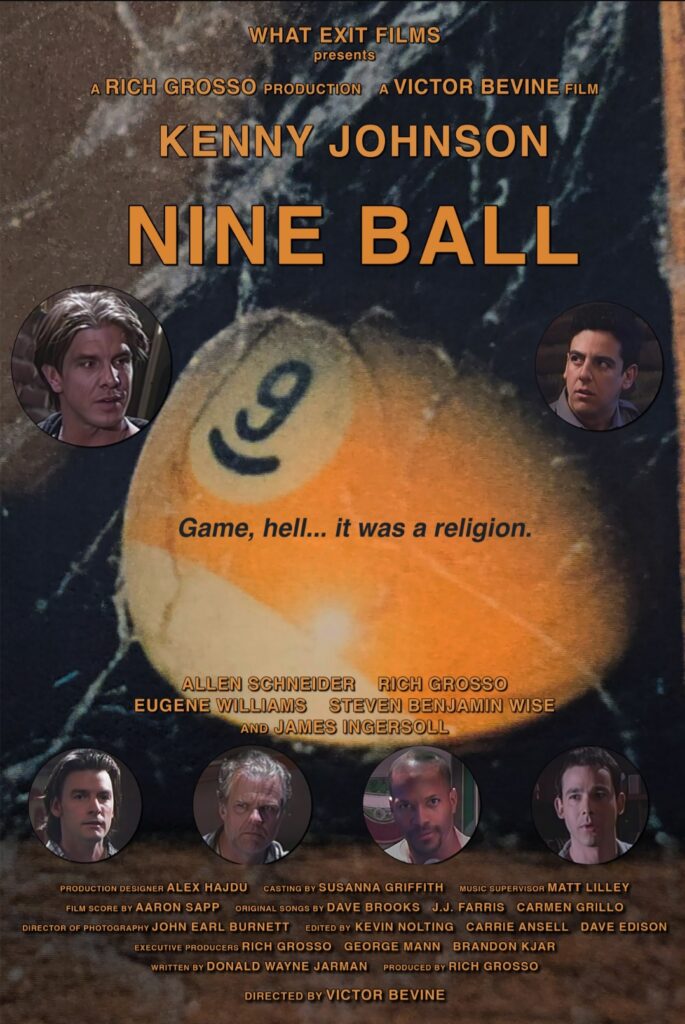

They just don’t make them like this anymore. A vintage roadhouse drama through and through, Victor Bevine and Rich Grosso’s feature film Nine Ball, takes things all the way back to the basics. Originally shot in 1995 but released only recently, this 85-minute Kenny Johnson vehicle certainly has all the ingredients laid out before it, but just can’t seem to blend these ingredients together efficiently.

In what is essentially an alcohol-fueled stroll down memory lane, an old and seemingly homeless Nicky (James Ingersoll) winds up at his own hangout spot after a nasty mugging incident, only to be saved by the establishment’s bartender, Doug (Allen Schneider). From the cobweb-covered walls to the black-and-white cinematography (John Earl Burnett), it’s clear something is amiss in the grand scheme of things. Doug transports Nicky back to his younger years of motorcycles and long nights that prominently featured games of pool. The two are joined by George (Rich Grosso), Bobby (Eugene Williams), and Cooper (Steven Benjamin Wise) for their cheery sessions, but as the nights get longer and the games get more heated, it becomes more and more clear that Nicky’s an odd man out in more ways than one.

Ingersoll plays a world-weary geezer, staring inward at a version of himself he barely recognizes. Kenny Johnson plays the impulsive, snarky bad boy version of Nicky to a tee. Imposing and unlikeable in equal measure, there’s a darkness to his character, clearly bottling up a lot of resentment. And as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that all his pent-up aggression is just begging for an opportunity to be unleashed, with his friends put in harm’s way. It’s this slow, but fiery descent into madness that Bevine and screenwriter Donnie Jarman choose to frame a devastating betrayal around, peeling back the layers on Nicky’s motivations as they do.

At face value, the film is very well put together. Well-placed tunes, solid camerawork, and colorful banter are mainstays, but where these technical elements work solidly together, the script fails to tie them all together. Jarman’s screenplay works best when it actively pushes to untangle this web of frustration surrounding Nicky’s past, but succumbs to a bunch of clutter along the way. Nine Ball is plagued by small talk in a large portion of its dialogue, with characters just rotating in and out of the scenery without much rhyme or reason. Each interaction feels like padding rather than substance for the story, throwing a promising and mysterious narrative into overlong and unnecessary territory.