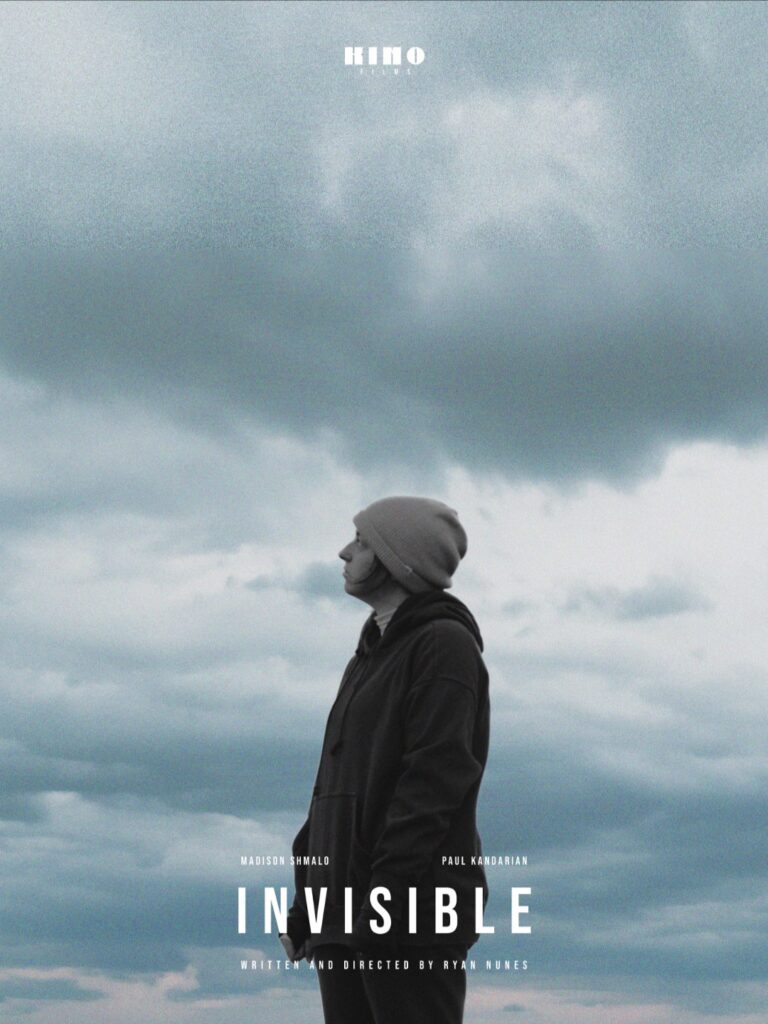

When life is a constant fight against pain, how can someone put on a brave face day after day? Writer, director, and producer Ryan Nunes raises this question in his short film, Invisible, about a young woman struggling to live with her chronic illness.

Best described as a character study, Nunes’s film follows Riley (Madison Shmalo) through the tedious revolutions of her day, each moment overwhelmed by the pain she must endure. As she tells her support group, the world ignores her, forcing her to plaster on a smile to make her presence easier for those around her. With each passing day she grows weary, her pain raising questions about whether or not she can survive this life forever.

As the film unfolds, it becomes clear that what we’re watching is less focused on plot than it is on character. After Riley leaves her support group, we become quiet observers of her life in its true form, pain and all. We follow her as she makes deliveries at her job, climbing up steps with heavy boxes and taking long pauses to let her body recover. Then she heads home where pill bottles line her countertop, a bright orange reminder of her body’s attempts at rebelling against her. One moment she is sitting on the floor fighting back tears as a wave of pain rushes in, the next she listens on the phone as yet another mindless insurance drone tells her they can’t approve her prescription refills.

But Riley isn’t the only one in this story. Her coworker, Jack (Paul Kandarian), adds thematic and emotional significance, serving as a mentor figure to her in a way that develops the world around her and reminds us that hope still exists. His presence, while limited, is poignant and purposeful, sprinkled in at the end of the film to allow Riley’s story the space to thrive and shine above all else.

What is perhaps smartest about the film, though, is its universality. Rather than define what illness Riley has or fabricate uber-specific scenarios, Nunes creates a character whose name is the only thing we can identify her by. We engage with the film and its protagonist at face value, seeing chronic illness not as something that affects this single person but something that is experienced by hundreds of thousands of people across the globe. From the moment the film begins with Riley’s monologue at her support group, we are encouraged to consider that this could be anyone we know.

Overall, the film asks us to observe without judgment, to put ourselves in Riley’s shoes (as much as we are able to)—and Shmalo’s acting makes this an easy task. Whether it is subtle discomfort or obvious pain, we are never in doubt of the ongoing hurt inside her body. We, as viewers, are asked to fully acknowledge the woman in front of us, unlike so many of the people in her life, and to let her be visible.

Invisible is simple in the best way. It doesn’t boast a complex plot, but rather serves as a window into the life of this young woman. As her job takes a toll, her insurance cancels her prescriptions, her job refuses her time off, and her body aches, we are left with an undeniable sense of how brutally painful living can be for thousands of people. . . and for Riley.