Satu – Year of the Rabbit follows the healing journey of two young Laotian children, and despite the painful digression of discovery, there’s a profound stillness to the presentation. So much so that it seems that not much is going on. But the powerful performances blend so seamlessly into the landscape that the events feel like they are actually unfolding. Ninety-three minutes of this deceptive calm, the net effect of the Joshua Trigg film is a monsoon of emotion that will blow the viewer away with joy and hope.

The biblical opening doesn’t even have the film straying from the paradigm either. After a mother perilously wades through a river – weaved basket, baby and all – we still can’t help being placated. The non-invasive fauna and the serene sounds of the natural setting and we become one with the production.

The mother (Sonedala Sihavong) does even more of a number. Her nurturing hum not only breaking through the fourth wall, you can almost feel Sihavong’s all encompassing hug of the baby.

Although, if you’ve seen The Ten Commandments, you know where this is going, and in this case, there’s definitely something happening. Baby is left at the monastery, and where Dara’s painful journey ends, Satu’s (Itthiphone Sonepho) begins.

A few years pass and the necessary crisscross of the main characters is on the way. Bo (Vanthiva Saysana) is a teenage girl, and the carefree traverse of her initial appearance is an absolute uplift. An aspiring journalist, Saysana’s youthful outlook evokes the possibilities, and obstacles are not yet part of her inner dialogue.

Still, the lightness of the introduction has denial down to a science. Entering her home, she’s careful not to disturb the darkness, and the evil that lurks inside. A drink in hand and cigarette butts littered about, Bo’s abusive father is an extension of the shroud, and the actor’s searing eyes and menacing exterior doesn’t obscure a fuse that could go off at any moment.

Bo’s prospects destined for the same, the score enters, and the guitar pluck contemplates the conundrum. Going up-tempo, though, the uncertainty is solved in the musical shift. The journalist leaves, and goes in search of her own story.

Her motorcycle providing the means of escape, she still needs to eat and stops at the same monastery in search of refuge and work. The first person she sees is a school aged Satu, and no surprise, there’s very little fanfare.

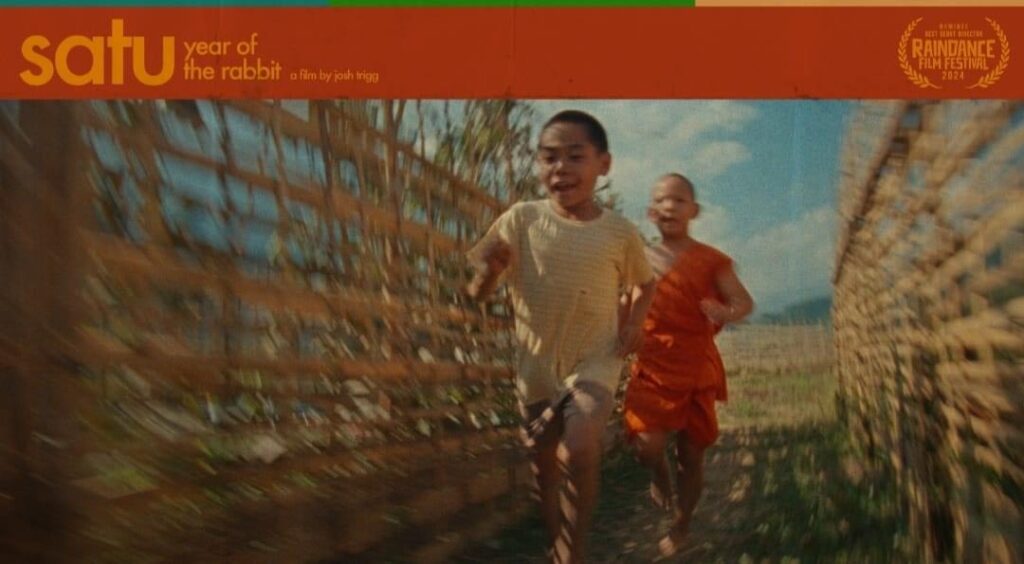

He’s unfazed by the unassuming visitor, and while she is endeared by his welcoming hello, fireworks do not ensue. Instead, they get to know each other, and the simplicity of their interaction draws the viewer into the duo’s orbit.

As such, he is beyond patient for a little boy, and for as much as we may like those who are all-boy, Sonepho’s laid back delivery presents a welcome respite. Alongside, she treasures the chance to nurture this dream.

But the mentor does so in a manner that respects the boy on his level, and painted onto the expansive canvas of the James Chegwyn’s cinematography, loneliness is the last thing you feel.

The sound department (Emanuele Costantini) plays a part too. The countryside traipse seems to pick up every broken branch, chirping critter and displaced piece of dirt and has the elevated decibel level seem like a watchful companion.

There’s a commonality that binds too. Bo is also dealing with loss, and the journey begins. They set out to find Satu’s mother, and of course, there are obstacles. But the paradigm remains, and the serene pacing still does not diminish your investment.

Even more so when their relationship is tested. This especially because we don’t know if the tandem has accrued enough of a connection to overcome the bump in the personal road.

Either way, they eventually reach the end of the line. Of course, like any meaningful journey, the destination is really the human heart, and by the time the credits roll, this movie really hits you right there.