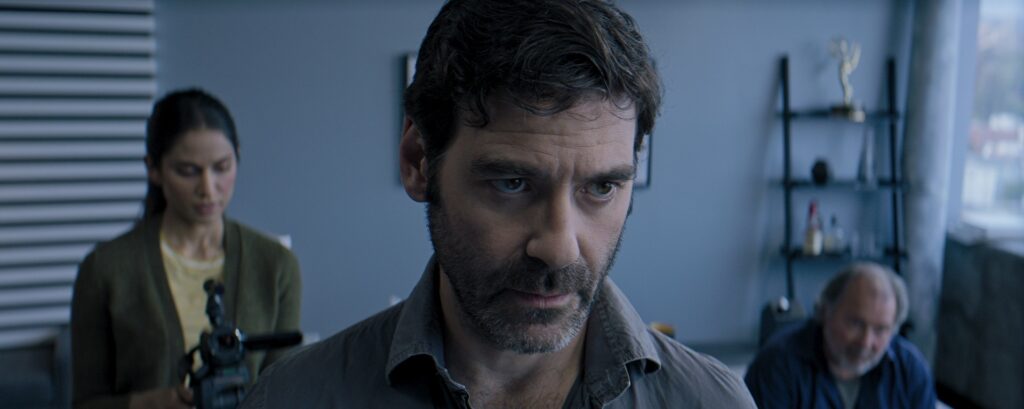

The very timely Award Winning short film Josiah, examines issues inside the creative process of a casting room, excavating unconscious stereotyping and complex power dynamics based on race, class and gender.

Where did you grow up?

In the small town of Berthoud, Colorado at the base of the mountains. Just outside Boulder.

What was your introduction into the Arts?

I worked at the local video store in my hometown throughout high school, which sparked an early interest in Hollywood filmmaking & storytelling. But it was in college at the University of Colorado at Boulder where I developed real love for film and experienced cinema as art.

Where did you study?

Undergrad was at CU in Boulder and I then attended grad school at the Film, Theatre and Television program at UCLA.

Josiah is timely. What was the impetus for embarking on the project?

I guess I would say to ask questions regarding specific creative processes inside the art of filmmaking, a medium of storytelling I very much believe in and love. The systemic issues in our society based on race, class and gender have long been themes of vital relevancy and we completed this project well before even the mass protests and movement we saw explode across the country earlier this year. With that said, we made the film because we were asking questions we didn’t have answers to and were seeking to take part in conversations where we could acknowledge inadequacies in our industry and even point out aspects of racism, sexism and even classism inherent in rooms where creative license is strongly preserved for those at the helm.

Where did this specific idea come from?

From a handful of experiences and observations about different aspects of the creative filmmaking process that I saw carried unhealthy power dynamics and life-altering ramifications. That may sound a bit dramatic, but I guess when it came down to it, I had been in a handful of rooms where a lot of mental gymnastics played out, including on my own behalf, in order to protect individuals who were deemed decision makers, specifically white males in positions of power. I think I became interested in exposing a breakdown that can occur in such a room based on issues of race, class and gender, where a white male creative was at the helm of a period project and in a clear power position, but possessed glaring insensitives despite having seemingly the best of intentions.

How were you able to get Kevin Dunn interested in the project?

I’ve been a fan of Kevin for a long time, so when my casting directors (Jenn Presser & Caitlin Well) mentioned him as an outside possibility, while I knew it was a massive reach, I couldn’t really see anyone else playing Jack. I needed Jack to possess a degree of charm but an overt and unforced sense of authority that Kevin naturally possessed in every pore in his being. We approached his manager to gauge availability, but his rep respectfully attempted to guide us in a different direction since Kevin was about to jump into a pilot and never really acts in short films. We were politely persistent and sent the script over anyway. Jenn & Caitlin woke up to an email the next day from his manager who had read the script and responded to it. I wrote a letter to Kevin for the manager to send along with the script and Kevin ended up calling me later that day. After our conversation on the intent behind the project and the discussion of Jack as a character, Kevin sent me a message that said he was in.

I assume people give a wide range of interpretation. What is it like to hear feedback that doesn’t actually align with your intention?

It’s definitely a challenging process to let go of the film that we hold so close to our chests throughout prep, production and then completing post production. In a sense, the film is simply no longer in your hands. When an audience member reacts in a different way then we originally intended, it can actually be quite healthy to remember that this medium of filmmaking & storytelling lives on the subjectivity of experience. This film, in particular, is about the collision of different perspectives inside a highly charged room, so hearing the feedback from different perspectives across the spectrum has been an even more revelatory process, one that has included a handful of different interpretations from what we were hoping to achieve, but hearing the truth from someone else’s perspective sort of validates the making of this specific project even more. We hope there is an extreme amount of tension and awkwardness when watching our film, but the reason for that tension and awkwardness can be very different depending on which audience member you ask.

How do you see that as a positive?

Simply put, it’s extremely heartening to know that we made something that ignites conversation. The film was sort of birthed from the notion that discussions about creative processes do not typically happen, and if they do, they happen in hindsight. Even if there are differing interpretations about particular moments, these different opinions/perspectives ignite more conversations about analyzing how we approach creative processes and the potential blindspots/flaws therein; many responses from audience members may have been intended, but there have been different reactions across the board that have absolutely led to conversations where even we became aware of our own potential blindspots as filmmakers.

How do you see that as a negative?

Well, sometimes you have to think about how you can execute something differently in the next project. If someone reacts differently than how you intended, there definitely may be an aspect of how you can sharpen the telling of a moment and become a bit more effective as a filmmaker. It’s the continual process of progressing as storytellers. Other times, the different interpretations add to the experience of certain viewers, so you chalk it up as a win and know there is a lot out of your hands when others embrace your films. And yet other times, you realize the subjectivity of experience for some individuals may hinder complete understanding of certain moments. We all have blindspots, some larger than others, and for those who lack any awareness of their large blindsopts, the film may have limitations in how it is perceived. Something you hope to help influence through empathy despite not having much control of, which becomes something else you sort of have to let go.

How do you read people based on what they take away?

Hopefully with little judgement, but I’m far from perfect. 😉 But in all seriousness, I have actually been floored by the responses, including the different readings and nuanced perspectives that I have heard from friends, strangers across the globe, even cast & crew members who have seen the film. There is definitely an openness of interpretation in this highly structured moment we observed in this casting session, but a lot of times the dialogue with audience members has been quite enlightening and heartening.

What were you looking for in filling the role of Brendan?

To put it bluntly, someone with serious acting chops. I’ve said it before, but I knew Luke had a deep reservoir and possessed some serious talent. He has the ability to move muscles in his face that allow for countless subtitles to come across and absolutely be felt. We had to enter into the room with him and, by the time we left, we had to feel like something potentially inextricable yet massive had shifted underneath us. I was hoping to find someone like Luke who could move the emotional tide in the room with powerful subtlety.

Mark? He was the Casting Director in the room played by Mather Zickel. I felt as though Mark was a bit of a showman, someone whose job it was to consistently put actors at ease once they entered into a room. Mather has that rare ability to present a warmth but instantaneously counter with a hint of deeper, genuine turbulence underneath.

Tina? Honesty and openness. An unscathed sense of what she felt appropriate that might not only point to her actual fault, but also be the quality we watch become damaged in the process.

It appears that the main scene is done in one take. How hard is that to pull off?

I think part of what drew a few people to this project, in regards to the cast and crew, were the extreme challenges we faced in pulling off this twenty-minute short film in three long takes, the first of which running approximately fourteen minutes, with only one day of production. I can definitely say that there was a heavy amount of preparation for our one day shoot and the emotional & technical challenges each of the actors and crew members tackled were quite immense. Especially for the Director of Photography, Jenn Gittings. When we completed the first long take that you mentioned, we knew we had a film, which was an extremely exhilarating and electric feeling on set right before we broke for lunch.

Tell me about the sensitivity on set of dealing with this issue?

We had several conversations with cast and crew members before anyone really signed onto the project. I think there was a high-level of awareness — including with my casting directors despite not having any auditions — in regards to making efforts to not cause any trauma that the film was attempting to expose. We had a discussion at the first rehearsal with the cast members and were hoping to make a safer space that allowed all the actors and department heads to bring their best artistry. But nothing is perfect and we only had a day of actual production, so the level of sensitivity to our approach perhaps was much more manageable than say compared to a period television series with a hundred cast & crew members.

What impact do you hope this movie has on viewers?

To take part in conversations. To ask questions. To analyze creative processes and acknowledge imperfection. To empower creators and decision makers with more empathy, awareness of their own blindspots and research. For us all to acknowledge there are very few rights and wrongs in our subjective medium. To listen and create responsibly.

What is next for you?

There is a feature script I wrote with my writing partner we are looking to get made that deals in similar themes of race and class. But as our industry continues to navigate the fallout from the pandemic, I’ll be actively producing a handful of television shows next that we are hoping to start production on as soon as things are safe.