London based director Julio Maria Martino sits down with Take2IndieReview to discuss his film directorial debut – Country of Hotels.

What were your inspirations to direct Country of Hotels?

Country of Hotels was conceived as a project between myself and the writer David Haupstchein. In setting about making our first film we consciously avoided using other films and genre conventions as convenient templates. Instead we aimed to create an experience for the viewer which was both idiosyncratic and genuinely mysterious, one which continually confounded narrative expectations and where the film lurched between unease and black humour.

Our primary/initial influences lay in the writings of 20th century artists like Kafka and Samuel Beckett who sought to plunge their readers into imaginary universes, giving voice to the sense of dislocation, loneliness and lurking fear which permeate modern existence, and offering only an absurd and blackly ironic sense of humour as respite.

That being said, in preparation for making the film, I also re-examined several films which took place in a confined location, and which had long been an inspiration to me: the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink and Polanski’s The Tenant and Rosemary’s Baby. Also, with regard to Polanski (along with David Lynch) I don’t think there has been a better director for filming “dreams” or a “dream state” and generating a sense of the uncanny. Rear Window was another resource and inspiration, in the sense that it dramatised so much of its story within the confines of a single living room.

Is the inception of the film based on experience, person, theme or something else altogether?

The initial idea for the film was of a mysterious hotel room which functioned almost like a central character (an “antagonist”) in a drama. The various protagonists are the hotel guests who check into the room and meet their reckoning one way or another; they go mad, disappear or meet an unfortunate end.

We picked a hotel room for reasons that were both practical and artistic. We knew if we were going to make a film it would have to be done on a micro-budget. But we also didn’t want it to be a low-budget, cinéma vérité movie, better suited to urban thrillers and social realism. Hotels are evocative, poetic places, not just in film, but also in theatre, literature and music. They are settings which can function simultaneously at a realistic level as well as a metaphysical one. You can step into a hotel, anywhere in the world, and often you aren’t entering a place that evokes London or New York, or Paris, but rather the “world of hotels”. A guest entering a hotel for the first time is very much a “stranger in a strange land”, so it’s the perfect location for an existential or absurdist drama.

The space is essential to the plot. Can you talk about the location findings and what was the process like to create the surrealism feel.

The film was almost entirely shot on built sets in a warehouse in Essex; an hour’s drive out of London. Everything you see (apart from a couple of brief shots in the television) was filmed on sets that were designed and built by our Production Designer Mike McLoughlin and his team. This includes the whole of Room 508, the hotel corridor and the hotel lobby.

It is gratifying when people who have seen the film ask me where we found the locations and if we used a real hotel. It means the film is convincing at a visual level. We constructed an artificial world, and we didn’t aim for naturalism, yet still wanted it to feel real to the viewer. Creating a credible “consensus reality” in a film like Country of Hotels is critical for the film to work. If your foundations are solid, then you can convincingly make the journey into the surreal.

Too often directors making surrealistic films commit a critical error. They signpost it, telling the audience that what is taking place is not real, but rather a dream or hallucination. Our golden rule for Country of Hotels was that everything that happens in the film should feel as concrete as possible. When Pauly hears the voice coming out of the heating vent or when Derek sees Louisa (from the television) suddenly sitting at the end of his bed talking to him, these events are shot, acted and edited as if they are really happening, without any stylization or special effects designed to signal the audience that they have now entered an altered state.

Filming on sets was critical to this. We could move walls; make holes and shoot through them; shoot from above; shoot from the other side of the bathroom mirror etc. It allowed us a much greater variety of shots that would never be possible in a real hotel room, and we could do things like subtly shift the spatial dimensions of the room, always with the goal of keeping the audience off balance.

Did you have a specific vision in mind for room 508? Were any adjustments made from the original conception?

The room had to feel like a churning and relentless vortex, inexorably sucking in its guests, pulling them towards their doom. That necessitated making a film which felt (to the viewer) like a very tightly controlled experience. The camera had to be the “all seeing eye” of the room, a voyeur, silently observing its inhabitants with its penetrating gaze.

Also, David and I were determined to create a film which had a timeless look. Although the characters are using mobile phones and laptops, there is a disorienting aspect to the hotel’s atmosphere and decor which stretches back in time. This furthers the impression that the spatial and temporal rules of the hotel are out of phase with our own.

Once these basic ground rules were laid out, I was open to discussion. One of the pleasures of working with a really great and resourceful production designer like Mike is that he was able to provide me with a huge array of choices and source all sorts of unusual objects and furnishings for the room and the wider hotel. Mike was continually innovating throughout the production. For example during the second week of shooting he began toying with the idea of creating an effect which made the hotel corridor appear endless when seen from one direction. This wasn’t something we had even discussed during pre-production, but Mike somehow figured out a way to do it (and with no need for post-production special effects, either, I might add).

When did you realize this was a topic you wanted to explore into film after having directed several plays around the globe?

I’ve always wanted to direct films. My father ran a number of VHS rental shops when I was a teenager, so watching films (and secretly wanting to be involved in making them) was something I did a lot while I was growing up.

Was there anything in particular that was challenging during the principal photography phase?

Low budget filming is like fighting whilst under heavy sniper fire! You have to keep moving – shoot, move, shoot, move, or you are dead. I quickly learned that in order to keep to schedule we couldn’t afford to get lost in the weeds of decision making too often.

But let me discuss another area which I found an interesting challenge: making sure I was useful as a director on set. If you have worked out your shot-list in advance with your DOP, and if you have a good DOP, a good Gaffer and a good First Assistant Director (as well as good actors) you can be in danger of finding yourself slightly redundant as a director once things are up and running, if you are not careful. Once or twice I noticed that the crew could pretty much get the basic elements of the job done without my input. So, I made sure I always thrust myself into the middle of the action, and I always tried to innovate with each new set-up. I tried to tease out verbal or physical improvisations with each new piece of dialogue or action, taking inspiration from the actors or props (objects) that were in the room. The rushes were full of this kind of stuff by the end. A lot of it we didn’t include, of course, but it’s surprising how much of the finished film includes unusual or unpredictable moments that happened on set.

With the Manchester premiere and the substantial changes happening in festivals going digital, describe your plan to expand the accessibility of the film to a wide audience.

We are hoping to play a few more festivals, and then we are aiming to agree to a distribution deal to release the film towards the end of the year (sometime around Halloween would be ideal). Manchester did an amazing job running a festival entirely online, but I hope one or two of these festivals will be live, physical events. These days it is relatively easy to get your film on streaming platforms (such as Amazon Prime etc) so that almost the whole world can have access to them. What is more of a challenge is distributing and showing the film in cinemas, where Country of Hotels works best. In a conventional cinema, you have a captive audience, and it’s not so easy to hit the pause button and fiddle with your cell phone. The cinema is an immersive experience, and because Country of Hotels functions on many levels, it requires a high degree of concentration in an environment devoid of distractions.

Country of Hotels premiered in the US. What were the reactions so far?

The best responses, for me, have been from people who were profoundly unsettled by the film, and intrigued by its mystery. One person told me that all along she assumed The Maid was a malicious character, maybe even evil and in league with the rest of the hotel staff. But, suddenly, at the very end, she felt a great pity for her. I don’t expect everyone watching the film to feel this way, but that sadness regarding The Maid was definitely something that we intended. We tried to build her story very subtly, so that she was almost unnoticeable as an important character until the very end. Any response which suggests the viewer carried on following the journey of the characters, and their various plights, to the end is great; anything which suggests to me that the world of the film is still circulating in their imagination the following day is wonderful. Our aim was to create an enduring mystery which you can return to again and again.

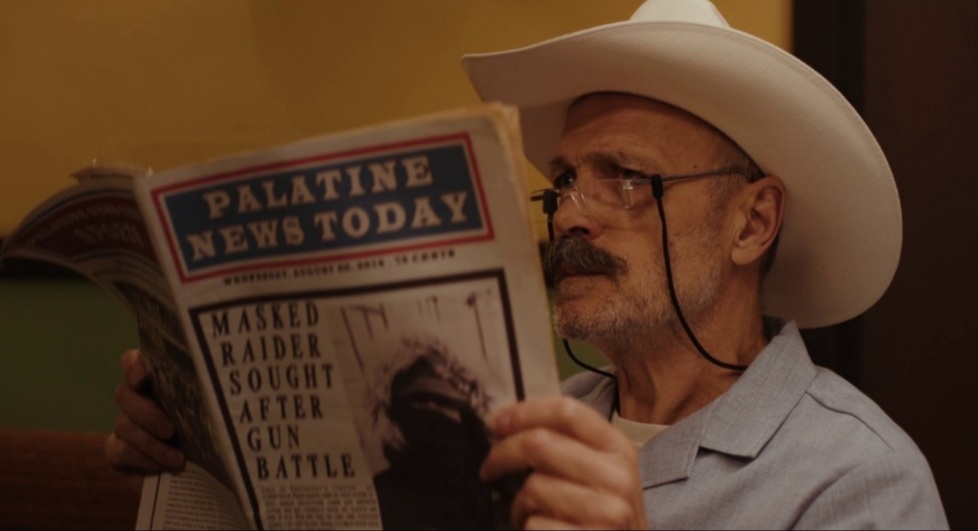

With specific regard to the USA, I’m pleased that no one who has watched it really questions where this film is from. It is set in the USA, albeit a very unusual alternate-reality USA. But it is a British film, filmed in the UK with a mix of British, Irish and American actors in the lead roles (and a multinational supporting cast). Yet no one questions whether it’s from the USA or the UK. People just accept it for what it is.

If you had one word to describe the film, what would it be?

If I was forced to pick one word: claustrophobic.

Talk about the casting process. How did you find the actors and how was the audition process?

I already knew about half the cast prior to shooting, as either friends and/or people I worked with closely before when I was a theatre director. By choosing people I knew and trusted, I felt free to be playful and to come up with innovative ideas. The first thing we shot was the standup comedian who appears on the television. He is played by Colm Gormley, an actor I have known since we were at University together. From the second take onwards I encouraged him to improvise and he started to come up with really funny, interesting stuff, a lot of which ended up in the finished film. (n.b. with regard to improvisation, I always try to keep the focus of the improvisation within the world of the film). So, when you hear him riffing, about taking himself out on a date, giving himself a cuddle and then having sex with himself, that is all Colm’s improvisation. Both the writer, David, and I really approved of this inventiveness and we kept it in the film – I think it acts as a doorway into the film’s more surreal and unpredictable elements (it also highlights the theme of narcissism which is very important).

The main actors (Hotel Guests, Staff etc) were made up of actors David and I already knew and people who were recommended to me by our Executive Producer Emily Corcoran (who has a lot of experience in independent filmmaking), and also some people who came from a casting call we put out. Everyone I didn’t know beforehand, I auditioned one way or the other; some in person and some via Skype (as they were working elsewhere). For a film like Country of Hotels, I think it’s important to make sure that the actors can tap into the absurdity of the situation. It’s usually the case that if the actor understands the black humour/absurdist elements of the script, then we’ll have little problem working together. One final thing to say about auditions – I always try to select pieces of the script which include the “extremities” of the piece. In Country of Hotels, several of the characters have to venture into the territory of abnormal psychological behaviour, and so I always asked them to read from something which demonstrated to me that they were both comfortable and capable of operating in that zone.

After your directorial debut, what advice would you give to aspiring filmmakers?

I could talk for hours about this! Presuming the person we are speaking about has no prior (or very little) filmmaking experience, and (like me) hasn’t been to film school, I would say the following; You need to find a way to create your own work. Getting experience working for other people (in whatever capacity) is always great and very useful. But, if you are like me, you may get bored observing someone else direct over a long period, no matter how good they are; unless that person is going to invite you into the creative process, which isn’t likely to be the case.

If you want to be a director, then you need to find a way to direct something. Ideally you should write your own film/short film as well as direct it, but if you don’t feel ready to write from scratch, then adapt something, or find a writer with whom you are simpatico. If you don’t know any writers, then go and see loads of fringe theatre, and I guarantee you’ll find someone with an ear for dialogue who is hungry to write a film. Design a film project that is within your means, even if it’s a “zero budget project’. Then, find a way to get it made. It’s a cliche, but there has never been a better time to make films for as little money as possible (getting them distributed and seen is another matter).

It’s always advisable to watch loads of films and study the ones you like; you must do this. But I think there is no substitute for learning by actually directing something. For me, it’s only when you force yourself into that position that your ideas suddenly come into contact with reality. At that moment, you are faced with trying to film “your vision”, which may or may not work. Once you’ve gone through this process (including editing and post production) you begin to watch and study films in a different way, anyway. Whatever you do, don’t spend years waiting for someone else (an agent, a producer etc etc) to give you a big break. It may happen, but it very well may not. Start finding a way to make films now, no matter how small. Don’t give yourself excuses. I gave myself excuses for far too long.