Nam-Hong arrives in Australia from Korea to begin a job as the head of security for Chandlerdale Exports, where something is inexplicably wrong. Still, Nam-Kong (Steven Whatmough) gains the company director’s trust, and the stakes get even higher when it’s apparent the company is at war with a cunning enemy. So what happens when the sum of internal and external conflicts exceeds one’s intolerance? It’s not pretty. So says the filmmaker’s synopsis of The Korean From Seoul. Sorry, they may have made most of that up, and finding a coherent thread in this film written and directed by Steven Whatmough is pretty hard. But the 88 minute film is listed as a comedy, and so off the wall is the presentation, that there’s no need (or possibility) to unravel the web this film weaves.

We begin on the serious side with our introduction to William Knoll (Ben Carew). The company director, the camera zooms in, and the screen fills us with a sense of an Aussie version of Gordon Gecko.

Mixed in with a dark version of James Bond, he stares us down. However, the idea of a villainous Australian makes it hard to keep a straight face, and the image must give way to something lighter.

So a company video for Chandlerdale Exports takes the screen, and the sales pitch is very familiar. Enthusiastic employees and graphics put on a human face on the company. Eased in from our seats, it’s very easy to miss that the actual discourse from Chien Ling (Pui-Mei Wong), Cliff Knoll (Andrew Pocock) and Erin Grass Forbes (Erin Carew) doesn’t make much sense.

The three supporting actors do a nifty slight of hand with the competing dialogue and the professional video work before you finally realize the nuttiness they are pushing.

Thus, the comedic stage is set for the rest of the lunacy, and Nam-Hong’s introduction to Knoll keeps the crazy train rolling. The tone is serious and the intrigue is built by keeping the shot cropped on the two players. In addition, the lack of background in this scene and throughout the direction implies that a singleminded expediency will be required for Chandlerdale to emerge unscathed.

Of course, there’s dialogue, and again to our delight, the imagery doesn’t line up with the words. For Carew’s part, his imposing CEO presence has us doing a double take alongside a stiff drink in hand and nonsensical discourse, while Whatmough does most of his work by quietly remaining aloof to the unraveling conspiracy.

There also seems to be some sort of message in regards to how the white Australians have interacted with the rest of Asia. You may have to locate an Australian or read up on your history to decipher the underpinnings. But either way, the disconnect is dealt with humorously and Carew deadpans early on with the cryptic social commentary. “But the misfortunate thing is that we have predominately English speakers – especially the white ones, like me.”

The film notes aren’t a complete fabrication, though. Chandlerdale is at war, and the declaration is so stated. The points of contention have something to do with cereal, train rates and an empty wooden security box, and the noir encompassing score by Whatmough keeps the doom ever present.

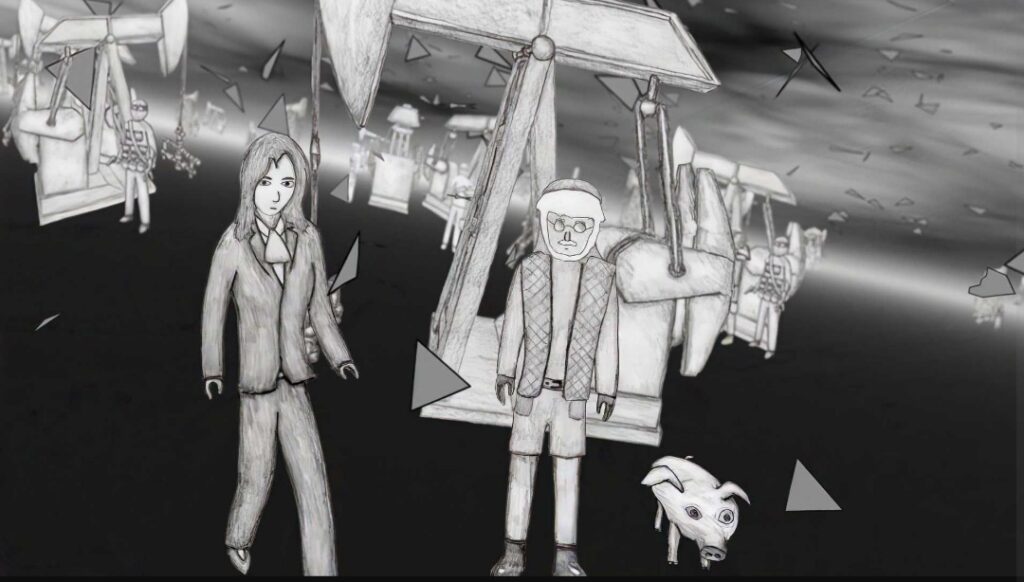

Several scenes that seem to allude to the Matrix designate the seriousness – and playing well to the lower budget special effects – the oncoming pseudo dystopia is built upon. Not to worry, though, William Knoll, Nam-Hong and friends have no idea, and neither will you. But you’re still going to enjoy this movie.