Where ever you were, 1968 was a year of tumult. The Democratic National Convention blew up in violence over the Vietnam War, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, and Europe had taken to the streets in mass worker and student protests. Included, of course, was Italy, and The Lost Shoes follows the revolutionary path of one Armando Lanza. A 104 minute documentary based on Lanza’s book, the Tomaso Aramini and Rafiqfuad Yarahmadi’s feature film brings us back to a fascinating time.

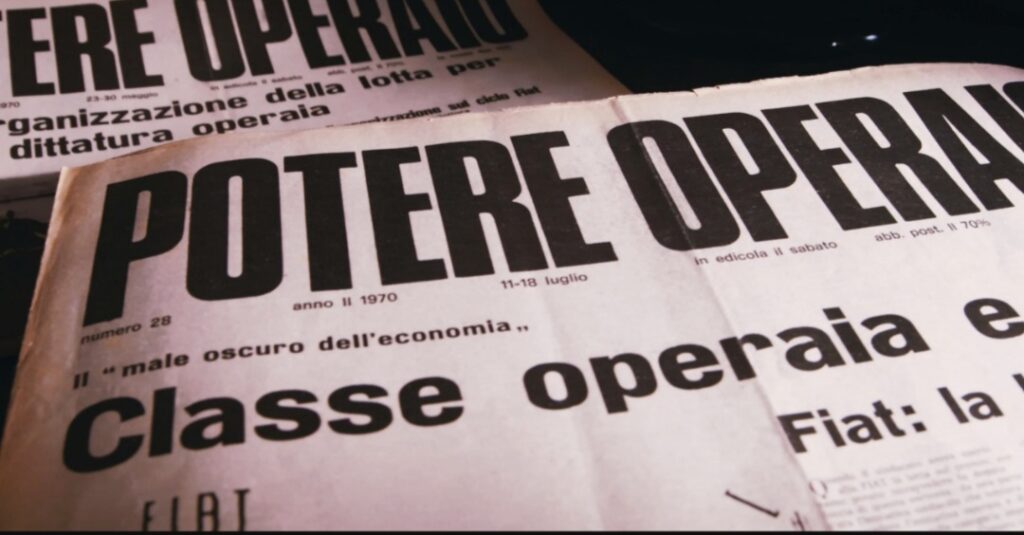

But with problems of our own, the upheaval probably remains unknown to most Americans, and the chance for education is front and center. The film begins with a clipping from an old Italian newspaper, and even if you don’t understand the language of the dramatic headline, the image lets you know revolution is in the air.

Then we meet Lanza on a news cast, and the larger elements of social change falls in favor of family. He has dedicated his book to his daughter so she can understand why he went to prison all those years ago. A very touching kick off, revolution becomes down home and personal.

So Lanza sits with his daughter, and against the backdrop of the sedate Italian countryside that Aramini produces with his cinematography, we begin to get an accounting that eases us into the past. Almost like a lullaby, Lanza’s path to the revolutionary left is revealed through his formative childhood experiences, life as a teacher and larger societal events. “I was about your age when I used to come here,” he recalls from a park bench. “The early 70s, at the time, we had a political group called, Workers and Student Collective”.

On the other hand, the fairy tale switches gears and goes up a notch with the introduction of documentary footage of the time. Students and workers in the streets, factory workers and farmers subsisting in dire conditions and violent clashes with the police – 1968 meant business and anything seemed possible, according to the imagery and the contemporary narration.

The purview then gets wider. Lanza’s reach extends with a trip to the war torn countryside of El Salvador and the movement begins addressing the Western Imperialism forced upon Vietnam, Latin America and Africa.

Unfortunately, the elevation the footage creates always comes back to Lanza and his old comrades. Not an exuberant Abbie Hoffman among them in the least, the old guard are some pretty boring revolutionaries, and the complacent recounting becomes a slog to stay focused.

You wonder if there was ever any fire and passion in accompaniment of the dramatic events. Either way, old age has taken over and the awakening this life presented for the players, doesn’t come across in the retelling. So it’s hard to be interested in their struggle, and the education the film is trying to provide.

Enrico Fenzi makes the case most significantly. On the Strategy Committee of the Red Brigades, the elderly sage makes the upheaval sound more like a political science lecture.

Of course, the various movements start to splinter and taking violence to the state becomes an option. Thus, Lanza makes his choice, and is among the kidnappers who took NATO General James Dozier in 1981.

In turn, Lanza feels the full force of a democratic government that oversteps its bounds, and the film definitely calls into question the brutal reaction by the establishment. However, the film does leave out some important context. The former Prime Minister (Aldo Moro), was assassinated by the Red Brigades in 1978, and completely omitted, the earth shaking national event should be part of the conversation.

Nonetheless, The Lost Shoes gives Lanza the space to express his part and the degree of regret/pride is open to interpretation. A meaningful ambiguity – but too bad the characters and pace yield a sauce that is in desperate need of some spice.