The intentions of Adrian Roman’s Oak on the Outside are so earnest, so pure, that it becomes difficult to criticize the film’s flaws, of which there are many. Jumbling a plethora of genres into one narrative, he aims to kill several birds with one stone, but misses most of them. That being said, some of the picturesque details and shot compositions alone render the film watchable, and sometimes enjoyable, despite the tonal whiplash.

The film starts with a series of news headlines about child trafficking, preparing the viewer for a penetrating, thrilling expose of the ongoing crisis. It soon becomes apparent, however, that “penetrating” and “thrilling” aren’t necessarily the adjectives to describe the unraveling events. “Sedate” and “maudlin” would do the film more justice.

PhD student Rebecca Livingston (Gaia Passaler) is making significant progress in the field of psychoanalysis. A true altruist, she has “enhanced empathy”, feeling what her traumatized patients feel – she even helps out the local homeless woman. “I appreciate what you’ve done for me,” she tells her (somewhat creepy) professor, Benjamin Graves (Treg Monty), “but I need to use what I’ve learned on real people.”

Graves reluctantly refers the young woman to the PTSD-stricken Captain Eli Stone (Brandon Scott Hughes), who lives on a farm. “This man came back from having battled the devil himself in hell’s front yard,” the professor warns Rebecca. Unfazed, she leaves her promiscuous boyfriend behind and heads to the countryside.

Upon arrival, she encounters the stiff-lipped Colonel Chafee Beauregard (Scott James), who brings her to her disheveled B&B. She soon meets the young Skylar Dailey (Julie Howell), a local farm-head and tractor technician – and a trafficking victim, who spent over three years locked up in a basement, prior to the colonel rescuing her. “That’s what [they do],” Skylar says, “they find us and bring us back home.”

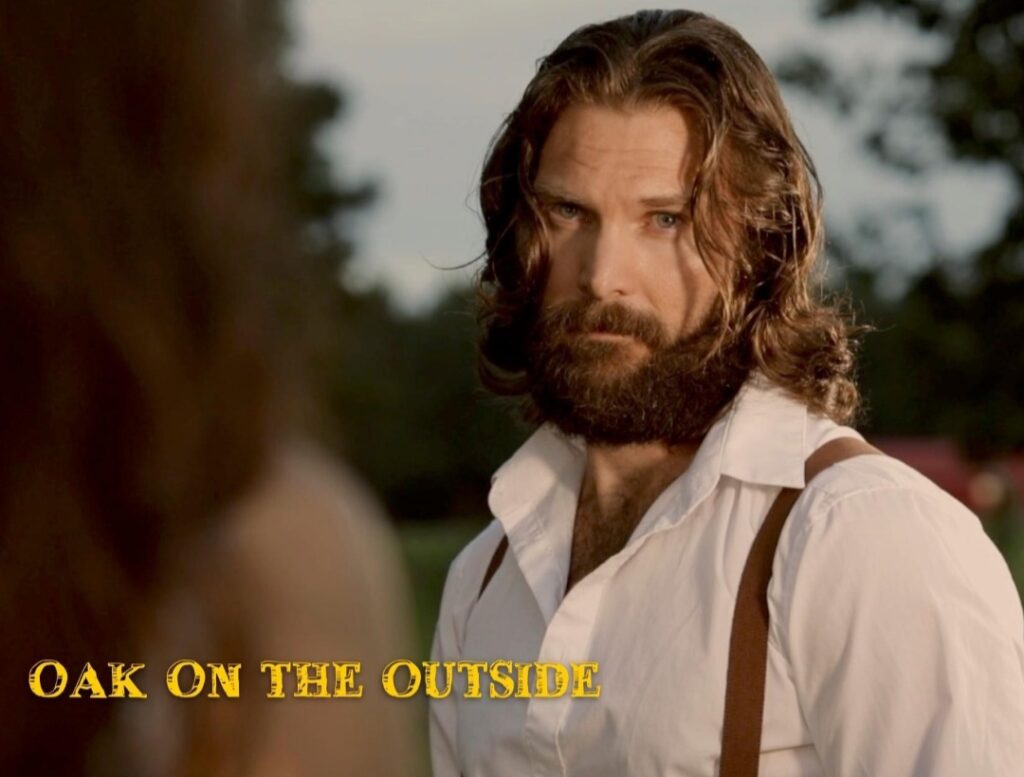

Captain Stone turns out to be a suspender-sporting, bearded, muscular hunk who seems to have stepped off the cover of a cheesy romance novel. Rebecca conducts her unconventional therapy sessions with the man. He’s reluctant and angry at first, but then saves her from lurking drug traffickers. Post-recovery, charmed by his gifts of flowers and necklaces, she initiates a tumultuous romance, attempting to break through Eli’s stoic veneer. A visit from local authorities, and dreadful news from back home, speed the narrative up towards the inevitable culmination.

Roman uses his very limited budget wisely. The writer-director (and cinematographer) is particularly adept at portraying farm life: well-composed, lyrical shots include Rebecca sporting a straw hat sitting in an emerald field, while a man emerges from a sunflower patch. Another image neatly separates the women and the men in the house. If only he took this dichotomy further and explored this sexual separation thematically, cutting deeper.

Gaia Passaler does her best in a somewhat underwritten part. Apart from her vivacious desire to help the traumatized, and her lust for Eli, there’s not much revealed about what’s driving the protagonist; she’s a bit of a blank slate. Brandon Scott Hughes plays the reserved, distressed sex machine well; their chemistry is apparent, although it’s more of a gentle spark than a sizzling maelstrom of passion.

Some amateur/stilted acting, editing inconsistencies, and sound issues make the narrative stumble. The incessant score keeps reminding the viewer how to feel. The mix of romance, drama, some elements of horror (!), and more specifically post-war / post-trafficking stress disorders doesn’t quite gel. Little moments pull the audience out of the story: Skylar divulging the worst thing that could ever happen to a person to Rebecca the minute the two women meet; Eli pulling on a pair of jeans after a swim, without drying off (not advisable); and the contrived ending that attempts to pull it all together, to name a few.

The film’s dialogue marks both the low points and the highlights of Oak on the Outside – the former due to its atrociousness, and the latter, well, due to its atrociousness. A lot of it is unintentionally hilarious. “When you’re alone, you have demons that crawl out of the darkness to torture you, don’t you?” Rebecca asks Skylar. “It’s easy to be around without people,” she states at one point. “I was thinking that ice cream makes everything a lot better,” Eli says (ah, the old ice cream adage!).

While Roman never quite makes his story sing, the tune it hums is intermittently compelling. Perhaps if he just focused on Rebecca guiding Eli out of his PTSD, or the child trafficking, or the romance, or how the countryside heals city wounds, it could’ve been a charming, albeit very lo-fi, little film. As it stands, it’s worth a look, but starts to disintegrate upon closer inspection.