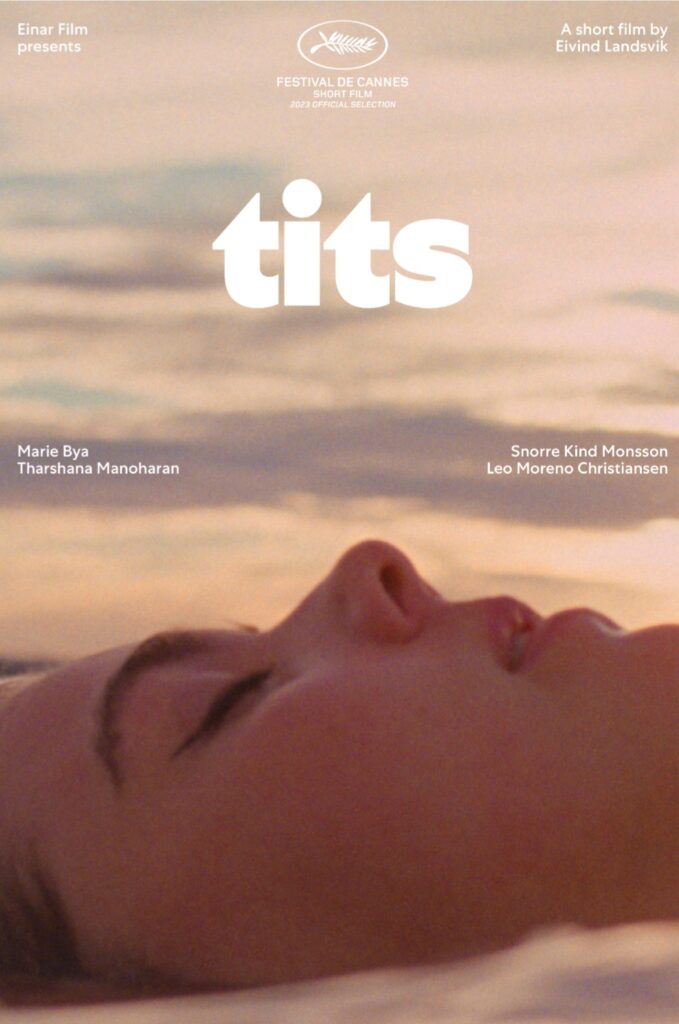

Tits, written and directed by Eivind Landsvik, is a visually stunning coming-of-age tale. The film mixes sea, sun and self-consciousness in a truly marvelous and arresting way; it captures universal adolescent feelings and experiences—body confidence, social anxiety, experimentation with alcohol and cigarettes—and places them within a relatable and concrete situation. The film has a tinge of nostalgia, it is grainy and sunkissed, golden and enduring. It drifts through you like a memory, but has the lasting power of a punch. Tits gnaws away at your insides and gives you butterflies at the same time. It is a teenage existential dream.

We are first introduced to teenager Oscar (Snorre Kind Monsson) as he’s getting ready to go out. He’s looking at himself in the mirror, meticulously gelling his bright ginger hair. There’s a song playing in the background, muffled, as his focus is razor sharp on the reflection in front of him. He is pulling at his clothes, making them fit better, weighing up the color coordination. He smiles at himself. He’s made an effort, and he thinks it will pay off. The film then cuts to a girl, Iben (Marie Bya), also in front of a mirror. She’s posing, turning, trying to find the right angle: the angle to provide enough confidence and affirmation before leaving the house. She talks to her friend about boys, a specific boy, school drama, the trip to the beach. Oscar and Iben, from drastically different social standings, will cross paths and form an unlikely friendship.

The film takes place over the course of a day. Its drifting and whimsical style, conducted within a fixed place and time, is reminiscent of Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise or, more recently, Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person In The World. There are also elements of Claire Denis’ Beau Travail, particularly in the way the film captures landscapes and physical movement. Most of the film is set on the rocks at the beach, right next to the sea: the huge expanse of water reaching out towards the horizon. The ambient and natural sound design—a combination of sea, wind, water, splashing, birds—is subtly enveloping. Though it is easy to be consumed by the stunning environment, captured superbly by cinematographer Andreas Bjørseth, the film is predominantly about people: namely, young people whose identities are still very much in genesis.

Tits gets the pressures of being an insider and an outcast. The film pivots well with a perfectly constructed moment between the two main characters. Though we don’t condone what is said, we empathize with both the aggressor and the victim. The film understands precisely how spiteful words can ruin a happy day (or evening); how spiteful words can completely reconstitute events in our head: reframe our perspective of ourselves. Words can be like daggers, piercing through our comfort blankets and coping mechanisms. Words can steal smiles off of faces, bury a newly bought t-shirt at the back of a wardrobe, prevent people from taking part in activities altogether. Tits acknowledges the harsh world of adolescence: the words, looks and interactions that form who we are and who we will become. But, crucially, the film offers a hopeful solution: a glimmer of a possible path towards deep connection.

Tits is masterful in its combination of story, cinematography and performance. Its understated emotional weight mirrors the tentativeness and suppression of teenage years. It is a tale of varying forms of anxiety—about bodies, social dynamics, romance—that resonates universally, as well as being entirely grounded and human. The film answers the question of adolescent angst with a deeply moving connection. . . and compassion.