In Liam LoPinto’s The Old Young Crow, poetry transforms into the visual language of film in a beautiful and well-crafted meditation on youth, identity, and homeland.

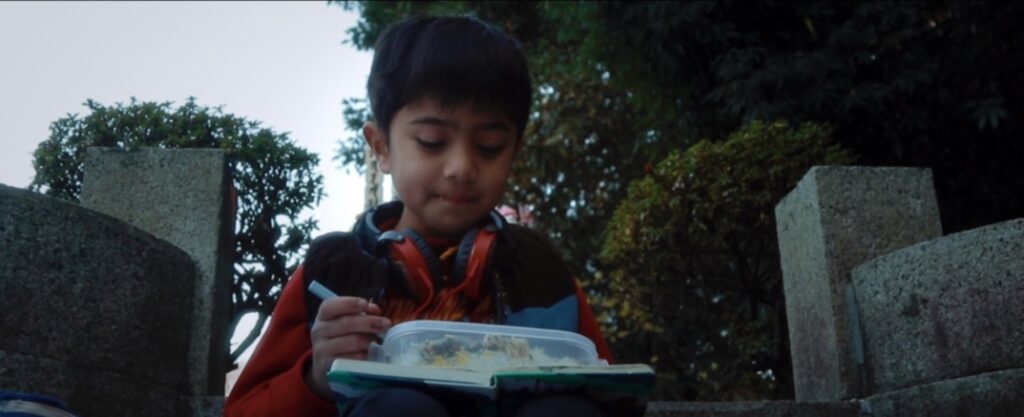

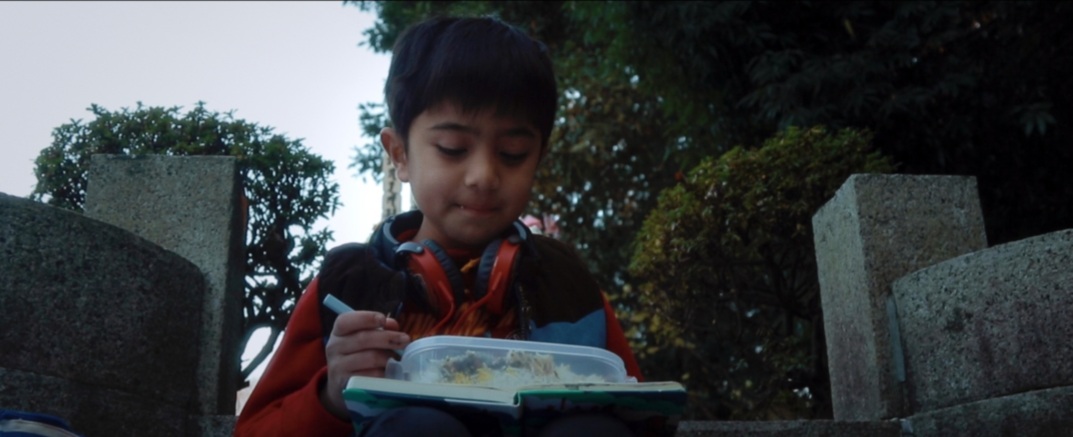

An old man named Mehrdad (Hassan Shahbazi) pours himself a cup of tea and tenderly flips open a sketchbook from his youth, setting into motion a documentary-style history of himself as a young boy (Naoto Shibata). After the passing of his mother, Mehrdad and his family move from Iran to Tokyo, ushering in a new stage of life as he searches for comfort and culture in a place he can’t yet call home. Mehrdad spends his time in a graveyard near school alone until the day he meets Chiyo (Keiko Yamashita), an old woman praying at the gravestone of her son Chiharu. The two share tea and conversation, but when Mehrdad returns to her house days later, any indication of Chiyo’s existence has long since disappeared.

Desperate for answers, he goes to the temple and seeks help from the Priest (Hitoshi Hinomizu) who tells him that the characters on the gravestone don’t spell “Chiharu;” they spell the name “Chiyo.” Mehrdad is unmoored, uncertain whether his conversation with the old woman was real or not. But after searching through his sketchbook for answers, Mehrdad realizes that the Japanese characters on the gravestone have a dual meaning: “Chiyo” and “Chiharu.” The old woman and her son share one name and one grave, like old crows with young souls. Mehrdad finally begins to see that he is one boy sharing two cultures, Iranian and Japanese, and both are a part of him.

LoPinto’s film is a poetic triumph, experimenting with form to tell an unconventional story about a young boy searching for home in a new country. Staged like a playful documentary, the film is more than just a generic past-present story; it is a genuine work of art.

What makes the film so artistic, though, is more than just its attention to detail and unique story. The Old Young Crow is a multimedia playground, filled to the brim with a childlike sense of wonder through its blending of normative filmmaking and various animation styles (LoPinto, Catharine Ren, Dax Wong, Sumin Cho, Cain Pickens, Tynan Wilson, Isa Hanssen, Drew Shields). Like something out of a modern art museum, LoPinto uses pencil, pen, digital, and stop motion animation to tell a layered frame story. As the old Mehrdad flips through his sketchbook from primary school, his fingers brush the pages and press hand drawn buttons to activate various animatics; Crayola drawings light up like neon signs, and roughly sketched forests are home to strikingly animated crows. This level of variety and interactivity feels wholly idiosyncratic, giving the audience the feeling of being there alongside Mehrdad as he recalls his time as a young boy. LoPinto’s artwork inside the sketchbook—from drawings of people and food to cats wearing crowns—literally jumps off the page, begging us to get lost in this experimental, artistic world.

The pacing of these visual elements is tightly bound to the score (Karen Tanaka), both of which fit together like puzzle pieces. We are swept up in the dynamic and orchestral Iranian song “Hejrat” (Googoosh) as old Mehrdad flips through his sketchbook until the stark striking of a match in the cemetery cuts out all music. The chaotic frenzy ends, replaced by diegetic sound and the soft playing of a piano in the distance as we leave behind the page and enter young Mehrdad’s world through the lens of a conventional camera. Simply, as the animation ebbs and flows with the movement of the story, so too does the music, ensuring that nothing ever feels stilted or out of place. The interaction of the two makes for a stunning watch with powerful forward momentum that is supported by a deep wealth of emotional significance.

More than these technical elements though, The Old Young Crow is a poetic meditation on the nature of home, identity, and the intermixing of the two. With help from the spirits of Chiyo and Chiharu—both embodied in the graveyard crows—Mehrdad realizes that he hasn’t been separated from his native country, he has just been given a chance to build a home somewhere new. While Japan believes in the spirits of nature, Iran believes in weaving nature itself into patterns and textiles. The two beliefs appear contradictory, but Mehrdad learns to blend the two: the spirits of nature, the crows, are woven into sketchbook patterns, pages, and pen marks.

This realization extends beyond young Mehrdad, though. While we never see more than old Mehrdad’s hands, we feel his presence through his narration and his interaction with the sketchbook; as we watch young Mehrdad search for answers, there is an inherent connection created between the two that reminds us these people are cut from the same cloth. And, in the final moments, old Mehrdad paints his own page in the sketchbook, adding a piece of himself to the last page before closing the book.

As The Old Young Crow draws to a close, we are reminded of the importance of language in Mehrdad’s story. Japanese and Iranian characters pepper the pages of Mehrdad’s sketchbook and the dialogue throughout, and the blending of the two cultures culminates in the film’s final revelation: that there is perhaps more than one way of looking at the words etched into the gravestone. The linguistic reveal is poetically coded, perhaps not intended to be completely understood by the audience. But the emotions that arise—the feeling of hope in the face of life’s uncertainties and changes—are clear, reminding us of the care and thought LoPinto has invested in telling this story.