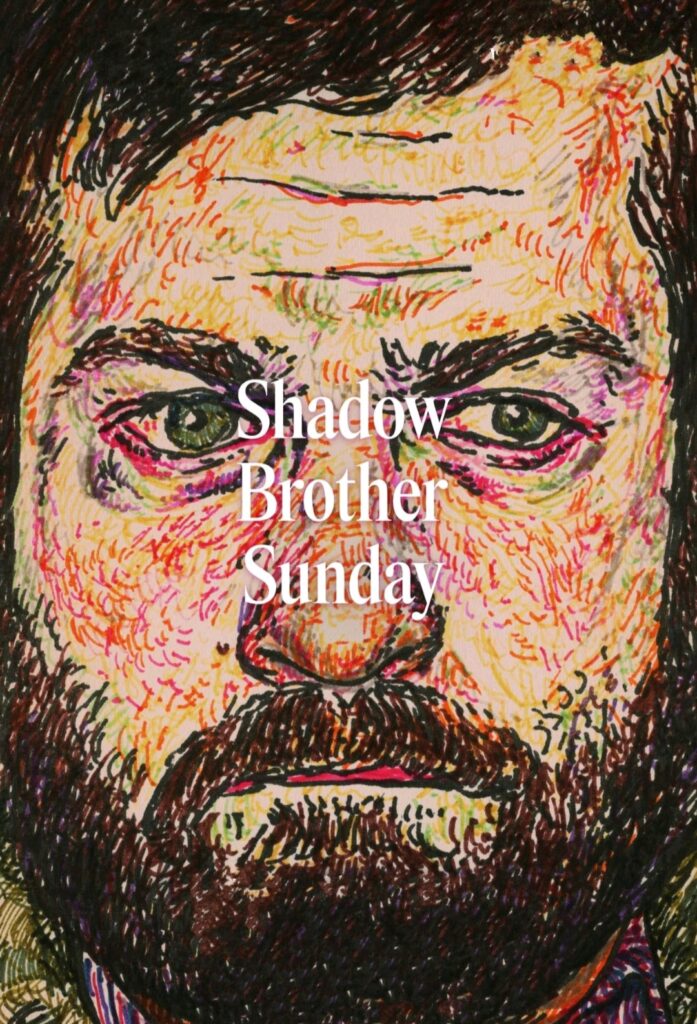

Family means only so much when they won’t help you with the rent. In his short film Shadow Brother Sunday, writer and director Alden Ehrenreich returns home as the family disappointment amid festivities celebrating his movie star brother.

The entire family has gathered for a pre-party celebrating Jacob (Nick Robinson), but the downtrodden and depressed Cole (Ehenreich), sees the party for what it is: a reminder of how poorly his life is going compared to his brother. But his fortunes may be changing when Cole gets a call from the paparazzi offering him eighty thousand dollars for private information from Jacob’s personal computer. Cole is hesitant, but seeing no other way to solve his financial problems, he steals Jacob’s computer and attempts to download its files without the rest of his relatives finding out. Taking refuge from his chaotic family in his car, Cole discovers an unsent email to himself in which Jacob, a young man riddled with anxiety, hopes he and his brother can be as close as they used to be. Cole is overcome, but when Jacob finds him in his car with his computer, reality sets back in.

Ehrenreich’s Shadow Brother Sunday is a tension-riddled rollercoaster careening headfirst towards either an emotional catharsis or an emotional disaster. Succinctly written and well-paced, the story knows when to humor its audience. It picks up speed in an almost a slapstick manner as Cole bounces between mothers pumping breastmilk or tweens in desperate need of a bathroom. The film also slows things down and reminds us what’s at the core – an imperfect relationship between brothers.

Both Ehrenreich and Robinson’s acting is subtle yet powerful, successfully embodying in their respective ways, a deep sense of discontent and the feeling of an interminable distance between the brothers.

The sound design and music stands out too, from the loud chaos of the family’s pre-party shenanigans, to the quiet tinnitus-like hum in the background as Jacob refuses Cole the money he needs. Not to mention as the film reaches its climax, a drum beat mixes with chaotic dialogue and loud background noise to establish an unavoidable feeling of pandemonium. There is an inescapable sense of forward momentum that only slows when Cole reaches a low point upon overhearing his brother’s conversation with their mother (Lisa Edelstein)—the same moment that shifts the film’s tone to something far more introspective and quiet. Simply put, sound and visuals (Ben Mullen) are beautifully united here, working together to create a consistent tone and pace for the audience to immerse themselves.

Ehrenreich’s writing is also extremely efficient in how it reveals information about this dysfunctional family, using short scenes and distinct character pairings to fully develop this family unit and its misgivings about their son. Cole and his father (Nick Searcy), for example, speak in a painfully candid manner that clearly lays out the tension between them and the disappointment he’s brought on his parents; in so few lines, the conversation escalates towards an uncomfortably truthful climax when Cole wonders aloud, “When is it ever about me?” His father is quick to shut the conversation down, answering the question for us: it’s never been about him.

Ehrenreich should be applauded for his refusal to let us side only with Cole. As the film draws to a close, we shift to Jacob’s perspective, watching him enter the house with a wide smile plastered on his face as his family surrounds and praises him. We hear nothing—not the kind words of his family or the delightful sounds of a party—except for a dull background hum and a voiceover from Jacob about his anxiety. We suddenly realize that what may have appeared glamorous at first is nothing of the kind. To rewatch the film through this point of view is a fantastic choice that complicates how we feel about our protagonist and the choices he’s made in the film.

What is perhaps so intelligent about Shadow Brother Sunday, is its use of the computer that Cole agrees to pawn off to the paparazzi. The object drives the story forward, yet it’s nothing more than a macguffin that exists for far more meaningful character beats to develop. In the end, Ehrenreich’s film is about family dynamics, both good and bad, and the computer puts Cole into situations where he has no choice but to face people who can’t help but put him down. It is a reminder of the rift between Cole and Jacob, but it is also the thing that shows us how they used to be and how they could be again.

In essence, Ehrenreich’s film is structured to engage us through awkward scenarios that make us laugh, but the emotion that lies beneath the surface—that pushes these brothers closer and closer towards an irreparable division—is what keeps us watching until the end.