Diarmuid ‘Derm’ Donohoe is a filmmaker and screenwriter whose work has spanned the course of two decades. Raised in 90’s Dublin, this multihyphenate has made a career practicing a variety of artistic disciplines, including classical animation (which he studied in Ballyfermot College of Further Education) and video gaming. He has directed many episodes of animation for large scale streaming networks such as Apple and Disney, and recently, his work in live action storytelling has garnered praise among prestigious film festivals worldwide. Diarmuid has also helped cofound ‘Shining Future’, an Ireland-based production company dedicated to helping tell Irish centric stories as well as genre and arthouse pieces. Take2IndieReview sits down with Diarmuid to discuss his career and his film Uroboros.

You grew up in the 90’s in Dublin — what elements of that environment do you feel influenced how you work creatively?

90’s in Dublin had an air of angst and cultural change about it. Hip-hop and skateboarding culture blossomed and I embraced it, shooting little skate videos around my local town. However, over the decade, drugs, especially heroin, started to flood the city and many of my friends swapped out their skateboards for tin-foil or a needle. That inspired my first short film Hot Knives. On a more positive note, world cinema became more available through independent video shops and I spent a lot of time watching Hong Kong and Japanese films. It was a great decade for an introduction to cinema. Channel 4, a UK broadcaster, would show week-long movie seasons from around the world. Independent Theatres like The Screen Cinema on Hawkins Street (since demolished) embraced world cinema too and it was there I watched La Haine, who’s angst resonated with me and inspired me to want to make films.

Diarmuid at 13 years

Your film Uroboros is dedicated to your Grandmother and other women who were wrongfully committed to mental institutions in Ireland. When was the first time you recall learning about this part of your family history, and what made you want to tell it as a story?

Growing up, I’d been aware of my grandmother’s “nerves”, as they say in Ireland. A euphemism for anxiety. When she passed away, we discovered that she had spent some time in a mental institution for no apparent reason and it had a lasting effect on her. All efforts to uncover the truth seemed in vain due to either hidden or lost records. The only information, at the time, was that she had gone to visit her parents for a week. Then, days after my grandfather dropped her off, he received a telegram in the factory in which he worked, to inform him that his wife had been admitted to St. Lomans in Mullingar. Needless to say, he downed tools and took her out of there. She apparently wasn’t the same after that. I think it was my mother that suggested writing a story about it in the end and I was honored to try.

Granny and Mam as a baby

What was the research process like for writing this film and deciding where to shoot, what the production design would look like, etc.?

The research was grim to say the least. A lot of the information on the asylums in that period was difficult to find, likely due to the fact that they were state run. Our health service, I’m sure, wouldn’t want that history to be publicized like that of the Church scandals. I did find many anecdotes online and there had been articles written over the years highlighting it, but it never seemed to have expanded into the public sphere. There was even a documentary called Behind the Walls that aired. I guess the Irish attitude to mental health is still a little detached.

Locations were difficult to find. Many of the old Asylums are available but the Irish health service shut us down continuously. I wanted somewhere that we could create sets for the wards, corridors, bedroom and living room in the same location and ideally an exterior that had the grandeur of those old buildings. It was actually our first AD that became de-facto location scout and after searching the country, she eventually found a school in Waterford that had everything I needed. She also found the lake and Church close by so everything was within a 40 minute drive. It was all very last minute but we lucked out for sure.

Production design was researched over a couple of years since the first draft of the script. I’d actually found a series of photos of some of those abandoned asylums in which beds, laundry carts, cabinets etc. were lying about decaying and imagined what the place would look like as new. A friend of mine painted up some concept art too and over time I was able to picture it. Helen Garvey, our costume designer, was amazing. She had a great understanding of the clothing of the time and pulled it all together. The main thing I wanted was a realistic depiction of the time and not a grim caricature. The story would be grim enough.

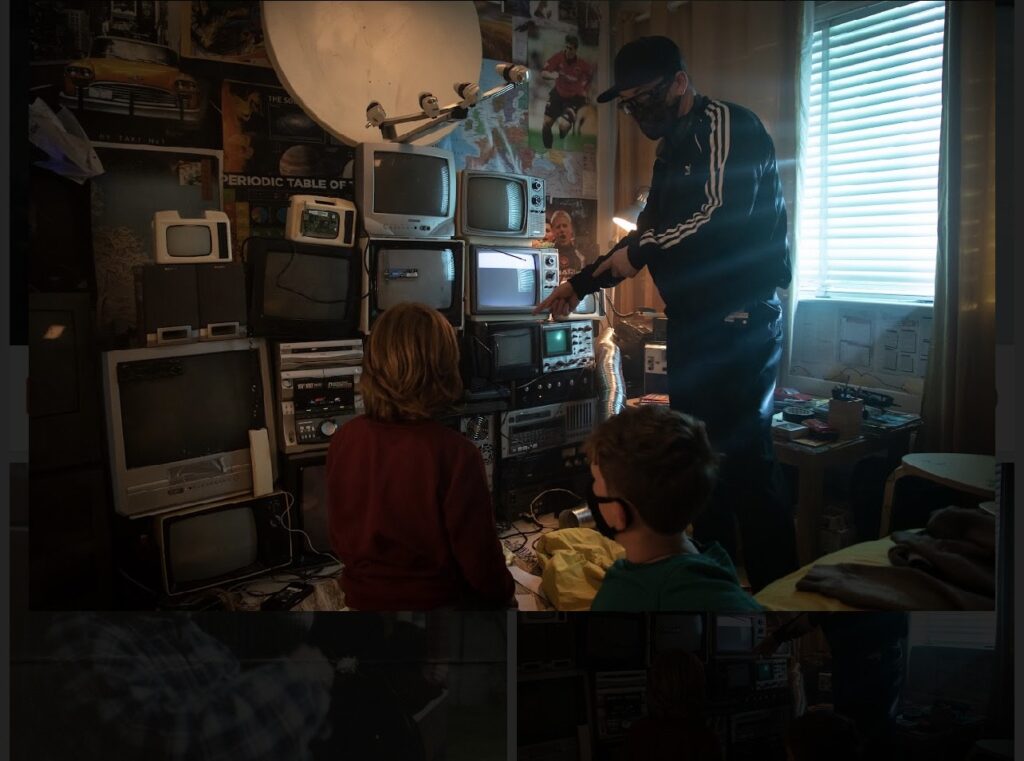

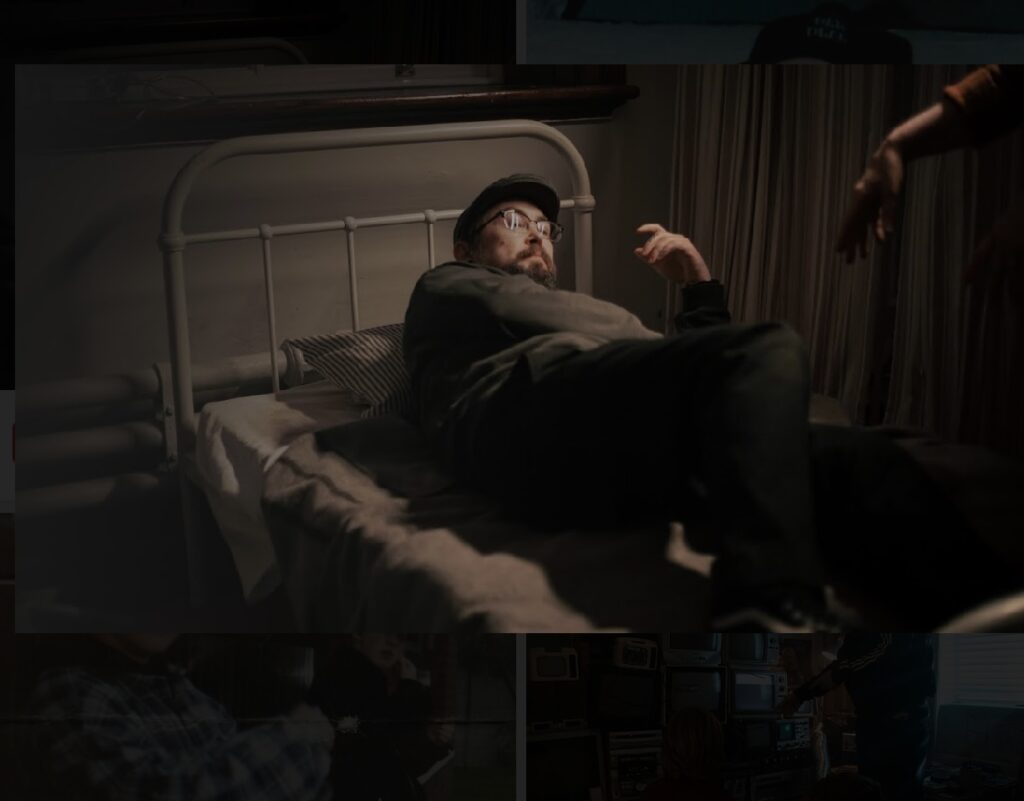

Directing on Signal

You are something of a multihyphenate, having done work in multiple different fields, such as video games and animation. What about this story made you choose live-action film as the medium to tell it?

I’ve always wanted to direct films since I was young. I fell in love with animation too but when I think about it, it was always anime from the 80’s and 90’s and it was the wild stories and cinematics that I was interested in. Nothing like that was available through live action at that time. I sort of got into animation as a career accidentally. Working as a filmmaker in the 90’s to me, was akin to becoming an astronaut, so I’d never given it a chance. It was actually my mother, who saw a meaningless and wayward kid watching anime, that literally filled out the forms for me to go to animation school. That said everything. I write with live action in mind. I feel it’s a stronger medium for delivering realistic drama and aesthetically it just moves me more. Sometimes I lament that I took the wrong path but I’ve learned a lot and I’m hopeful that there’s time left for me to do what I’ve always wanted.

You credit La Haine and Akira as two films that began your obsession with movies, and cite dreamy visual and seventies-style transitions as signature elements of your filmmaking. What are some pieces that inspired Uroboros, both visually and narratively?

Narratively, I wanted to create something nonlinear from the earlier drafts of the script that I’d written about 5 years prior. Turning it ‘dreamy’ was likely inspired by my love of David Lynch and the transitioning in and out of realities, in retrospect, was probably inspired by Satoshi Kon’s films like Perfect Blue. Visually I don’t know if I referenced anything in particular. I generally put together an array of imagery that suits the story and work them into the production with the team. I’ve always admired American films from the 70’s and though a lot of the techniques came from the French new wave, it is those movies that inspire me the most. For example it was the editing style of Don’t Look Now by Nicolas Roeg that inspired how myself and editor John Walters approached Uroboros.

Directing on Set of Signal

What compels you the most about storytelling through film that you can’t get with other artistic mediums?

Personally, what film does better than let’s say animation, is play with reality. I know that sounds like an oxymoron but what I mean is, if you’re watching animation, regardless of how immersed you are, subconsciously you know it’s not real. Live action for me, draws the viewer into a reality more comprehensively, and when that reality is skewed or distorted, is more impactful. I think that works for drama too. There’s something to a live human reaction that animation can’t quite replicate. In my experience, animation production is also quite rigid and controlled. There’s little room for happy accidents and I find the editing process in live action more creative. Animation on the other hand can do other things better than live action, or do things live action can’t. It’s just for me, and the things I want to do sit on the live action side.

What challenges did you face working as both a writer and director on this piece?

I can be a bit of a control freak when it comes to filmmaking, so being both writer and director suits me. For example, before principal photography and during rehearsals, we discovered some problems that required some extensive rewrites. I don’t think I could have handled passing that task onto someone else, so I was able to rewrite and rehearse on the fly. Also, having written the script allows me to know exactly where to go when it comes to problem solving during filming.

Describing Reverse Movement for Lacy Moore

How did you go about assembling your creative and production team for Uroboros?

It was difficult. Finding talent to work on short films can be frustrating because good crew tend to rise fast in Ireland. I had lists of various key people, but most were either working on big series and features or left the country. We were extremely fortunate to secure Narayan Van Maele as DOP. I think he’d just finished a feature and had shot the film An Irish Goodbye which won an Oscar weeks beforehand. The rest of the crew were hired organically through recommendations or who worked with either myself and producer Victor McGowan in the past. Victor also hired Dawn MacAllister as Casting director and she was incredible.

What was the most technically difficult part of creating Uroboros?

Locations. Finding the right locations was arduous. Ultimately, the location we used for the hospital and Moira’s home was the seed for most of the technical issues. The school is run by Christian Brothers and although they were lovely and accommodating, they didn’t understand the requirements of a film crew.

They failed to mention that they were hosting exams in one of our sets on one of the shoot days and had an Indian Baisakhi festival in full swing on one of the floors. It was comical, but put a stress on the production and we had to cut a lot from the film. We literally ran around the school with the camera on a Ronin in the final hours grabbing the coverage needed to complete the story. I’ve grown a few grey hairs from that experience.

Hospital Ward

One of the standout elements of your film is the terrific performance from Emma Dargan-Reid. How did you come across her as an actor, and what solidified your decision to cast her in the piece?

I had another actor attached initially who’d pulled out. Dawn Mac Allister, our Casting director, put together a long list of actors for the role. I narrowed it down to about 15 and got audition tapes from each using the bedroom scene from the script. Each audition was incredibly strong but Emma blew my socks off. To see her powerful delivery of the words that I’d written and imagined, was very emotional. Emma is a star and incredible to work with. Nothing phased her and she delivered the goods take after take. I look forward to the chance to work with her again soon. I must say the rest of the cast were top quality also. An absolute pleasure.

That’s a Wrap! – Diarmuid & Emma

Your production company, Shining Future, is dedicated to sharing Irish-centric media. What is unique about Irish film and storytelling that you wish more folks knew about?

We have a rich history and mythology in Ireland, and our way of looking at the world, I feel is pretty unique. There’s an abundance of art, culture and attitude to draw from and we have a wealth of talent here as evident from our presence in global awards. I feel that though Irish film and culture is strong, it’s just the beginning. The Irish people are natural storytellers and we have some of the most beautiful locations in the world. We have some of the best crew in the world too which is evident from huge productions like Game of Thrones, Vikings and Star Wars.

John Boorman once said about shooting in Ireland; “The light in Ireland has a kind of mystery to it. It can be very soft and misty, very hazy, and it can also be very dramatic and extreme, with these great contrasts between light and dark”. I think the same can be said of us as storytellers and with Shining Future I hope to be a part of the forthcoming Irish cinema.

What do you hope audiences take away after watching Uroboros?

It’s difficult to tell a large story in 10 minutes and part of the reason why it was told in a nonlinear fashion. Currently, I’m developing it as a feature because there’s so much of that world to bring to light. I hope that audiences walk away feeling a sense of the repression of the world in 1950’s Ireland, and ultimately the terror and inescapable confinement that thousands of people suffered during that time period.