Miki and Mimi are both actors who have a ton of passion for their art – and each other. They also carry a good deal of lunacy for their art and each other, and we follow the couple’s descent and discontent for 82 minutes in Maniac Miki, a Spanish film with subtitles. Yes, the emotional upheaval grabs us. But the vast disarray of behavior overindulges, and amounts to a lot of drama without achieving the irreverent critique of the entertainment industry that director Carla Forte seeks.

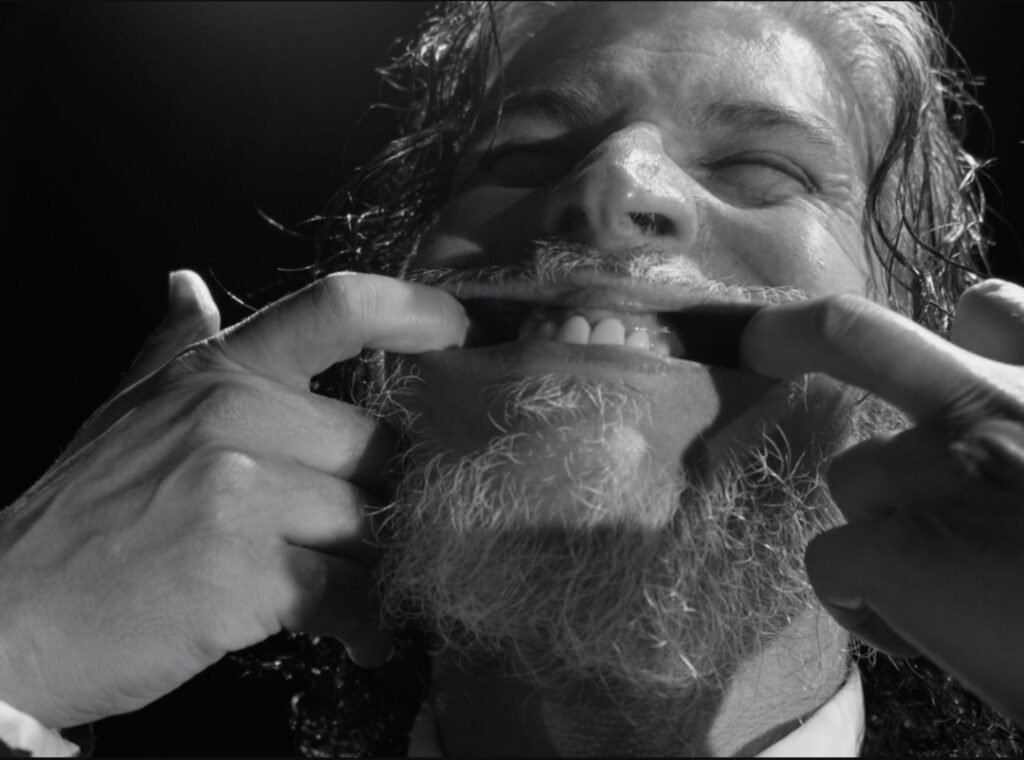

Thus, Miki’s children’s show has been canceled, and we feel the weight of the life altering moment through the power of Carlos Antonio León’s performance. The actor straddles the line between desperation and accepting his fate like a tragic comedy. In turn, we understand how Miki gyrates between the highs and lows as if he’s performing life like a movie script.

We then get a look at his relationship with Mimi and see a couple that loves to hate each other. For her part, Mimi (Lola Amores) is pretty maniacal herself, and quick to make demands and belittle Miki. Amores is equally fast to show her underlying and undying affection.

As such, Miki knows the drill and has no problem waiting out the tumult for the love that he knows is coming his way. An unending back and forth, their burdensome, yet fulfilling passion comes across in a very real way.

The baseline set, the film has us switching the scenery between the current timeline and a documentary film being shot about the children’s show that starred Miki. A natural in front of the camera, Miki is very impressed with himself, and when pressed as to who he really loves, Miki’s answer provides all the exposition needed – “Myself”.

Piling on, the off screen interviewer reinforces all Miki’s excess. Doing double duty, Forte keeps an even keel through Miki’s never ending nonsense, and the contrast helps separate the real world from the one occupied by Miki and his eclectic cohorts.

The choice of black and white film also plays a part. On Miki’s boat and on the set, the Alexey Taran cinematography implores that all the color needed will come from the characters.

But the well executed set up doesn’t necessarily work for our purposes. So in keeping with Miki’s character, he must continue offering long strings of dialogue that are only funny to him. The bad news is we still have to sit through them and watching León laughing, dancing, and self stroking his ego fails to entertain. More importantly, the bizarre behavior doesn’t really get us any closer to a real critique of the industry.

Nonetheless, we go on to meet a very strange blind mailman (Jose Manuel Dominguez), get a dose of Miki’s negligent mother and try to solve the mystery of the show’s long lost dog. More non-compelling lunacy, these are just extra fodder for Miki and Mimi to show off their excess. And just because they do so in childlike and irreverent matter doesn’t make the presentation something memorable or digestible.

It might help if the diatribes provided some revealing insight or actual humor. But without entertainment value or meaningful substance, the odd panorama tells us what we already know and makes the viewing a chore.