Diane Mellen, a Santa Barbara-based filmmaker, developed a passion for showcasing unique voices in film under the guidance of fellow creatives Bea and Sid Milwe in Westport, CT. Diane’s company, Pace Films, has overseen the creation of 12 documentaries. Founded in 2013, the production house has achieved great success, showcasing works at 68 film festivals worldwide and winning 30 of them. Alongside composer/mixer Jerry Deaton and director/editor Stacey Stone, Diane has focused herself entirely on vital social issues, such as mental health, the military, and the environment. Her commitment to telling “untold stories” has garnered plenty of appreciation and recognition. The NAACP recognized her as one of Connecticut’s most outstanding women with the Ruth Steinkraus Cohen Memorial Award. Diane’s 2023 film The Nona won Best Documentary at the Portobello Film Festival in London and premiered in March at the famed Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Her most recent work, Kenny, spotlights the homeless culture in and around Santa Barbara.

How was your early life in Connecticut? What was the culture like?

I grew up as a young child in Connecticut. I lived in a very small community. That was it. You had no choice about what you wanted to do or where you wanted to go. I got to know the Milwe’s, and they were very progressive. I’m laughing because I think about some of the things that they did, and they said to me, and still, one of the things that I remember the best was I read this article in the Connecticut Post about this man and, and his wife who had just donated their house for a black panther. The police in Bridgeport, Connecticut looked for this guy and said he killed somebody when in fact, he hadn’t killed anyone. And Bea went and found him. He was in New Haven, Connecticut, and she convinced him that she was going to have a lawyer present and make sure that he was safe. I read that. And I was always like, wow, these people are really great. I didn’t know who they were. And years later, my husband says, I want you to meet somebody, my friends. So we go over and spent a couple of hours talking with them, mostly about politics. And then Bea sits next to me and says, well, you know, we were in the paper. We had a Black Panther who the police were going to arrest, they were going to kill him. I said, you wrote that article? You were the one? And she says, yeah, it was me.

Diane in ConnecticutIn what ways did Bea and Sid Milwe contribute to your interest in film?

Bea was probably about 61 years old and went back to college. And once she finished college, she decided that she’d make her first film. At that time people in their sixties were not just starting making films. And she was very successful. She did one film, which was, about Castro. She was the first woman who went to Cuba to interview Castro. And she was excited about the film. She had to go to Canada first and then fly to Cuba because she couldn’t fly from the United States. I used to go to Bea’s house and I would climb up the stairs and she would have her nephew, Brett Ratner, who made films at that time, show one of his latest films and we’d discuss it. That got me very interested in films because it seemed very exotic. It didn’t seem boring, like a 9-5 kind of job. So, I decided I wanted, sometime later in my life, to try making films.

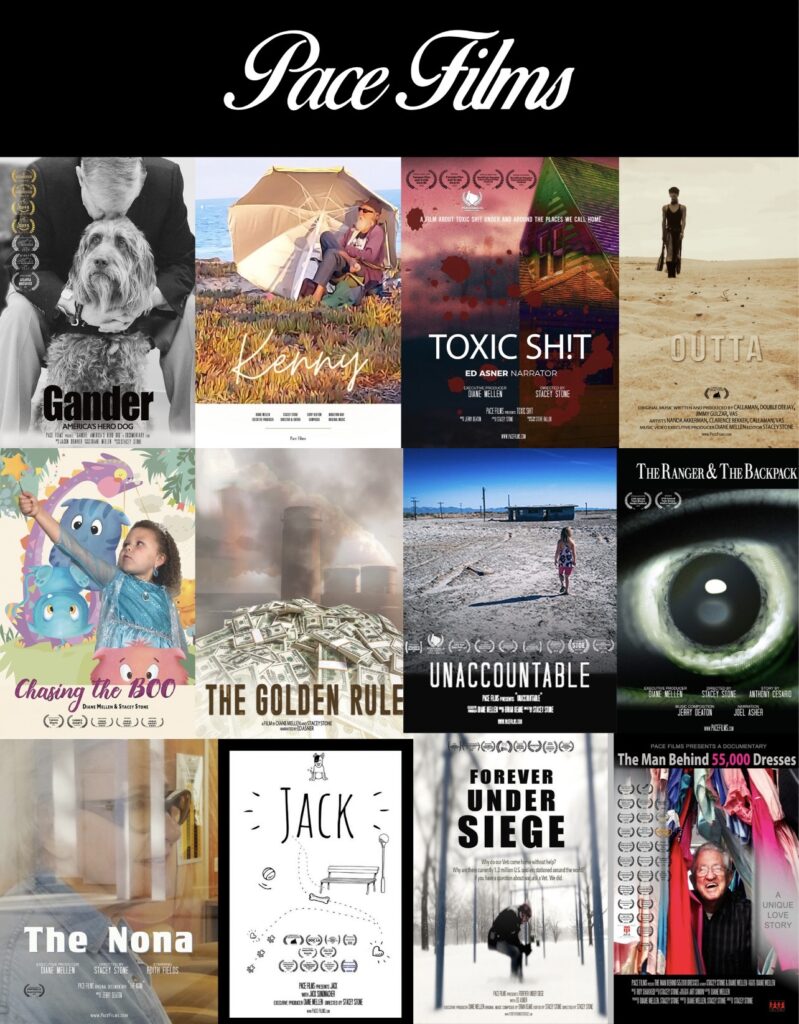

Bea & Sid MilweDo you feel like your company, Pace Films, has made a difference in the indie film industry?

All of the films we we’ve done have told stories that audiences probably would’ve never known about had we not brought them forward. And I think that’s why we do them. You know, everybody says you don’t have a good film unless it’s purchased by somebody. Well, let me tell you, you can have the best film made, but nobody picks it up. And why does nobody pick it up? It’s a great film, but it doesn’t have a big name or big budget. I want Pace Films to continue to make films that reflect humanity and raw truth.

What is the next step for Pace Films? How do you plan on elevating your platform to reach even more people and tell more stories?

We’ve been very fortunate in the eight films that we’ve made, we’ve received many accolades about the work that we do. We get reviews from different people who are in the industry, we get people who want to look at our work, they want to talk to us, they want to find out what we’re doing. We are working on a book which we are thinking about turning into a film. He’s a writer like Jack Kirouac. He’s a brilliant writer and his stories are unbelievable. We are increasing our platform and that’s a great thing. I think one of the most important things for us right now is that people are talking about Pace Films.

The Nona winning a top prize in London and then premiering at Grauman’s must have been a sensational feeling for you. What was it like to see your film get such a reception?

I have to thank Jonathan Bennett and Raymond Myndiuk for what they have done for the Portobello Film Festival and filmmakers throughout Europe. We were very taken by the creativity and edge of films screened and the risks they take as an independent film festival. It was nice of course, that we’d won but all the films that were selected were wonderful films. And, you know, I wish all of them could have won. I was happier about the fact that we were acknowledged for having been successful women filmmakers, because I never thought that people would take us seriously because we were not in our 20’s. We are two women filmmakers who wear a lot hats in our film company. We want to make a difference and tell unique stories and we were acknowledged for that.

What qualities do you look for in a good documentary? What is it that catches your attention and holds it?

It’s the story. The way it’s filmed. I like Citizenfour, the Edward Snowden documentary – it’s a powerful film and I liked the way it was filmed in the hotel room. It felt raw and real. And another documentary I like is Amy the Amy Winehouse documentary. They were able to show a lot of archival footage, and I really got a sense of who she was and what her life was like.

Kenny isn’t your ordinary documentary. How did you decide on the subject? What was the process?

We had met Kenny three years ago and walked by him on the beach. I noticed him. Stacey noticed him. I said, hello. She said hello. And then as time went by, we used to ask him if he needed any food, and we would bring food. We talked about different topics we thought he might be interested in, and he got to know us. And so that went on like that for about two years. And then I thought that he would be a great subject for a film because he was such an articulate man. And he was funny. He had a lot of stories to tell about himself. Eight months ago we started to film.

What was production on Kenny like? Were there any challenges?

Before I interviewed Kenny, I had come up with a series of questions that I would ask him, but it turned out that I didn’t need questions because he would just talk. I would listen to what he would say, and I would pick some kernel of what he had spoken about and go with that. And I would give him another question and he’d answer that. Unfortunately, we weren’t finished with the Kenny film, we had to go back to Los Angeles, and when we came back to Santa Barbara Kenny had disappeared. We didn’t know where to find him, where he would be. When we came back, we drove all around. I said, we’ll never find this guy. We’d drive underneath the underpass, down streets that he would stay. We couldn’t find him. And all of a sudden Stacey looked out of the car, and said, Kenny! And there was Kenny riding his three-wheel bike, down the street, crossing right in front of us. So, we had Kenny magically appear and finished the rest of the film and then he disappeared again. We’ve not been able to find him since we finished the film. And we’ve looked everywhere.

How did the concept of using hand-drawn rotoscope animation come about in Kenny?

We happened to see that style in Portobello, it was an animated short from France. And I turned to Stacey and I said, boy, that’s an interesting piece. It was called A Bicyclette. And my husband was so taken by that film. We talked about the style. And we tried to contact the animators in France who were attending an animation school in the south of France. We never heard back from them, and we tried to call the school and we never heard back from them. So, Stacey took a course and learned to do the animation on her own. Rotoscope animation has a very sketchy feel to it. The specificity of traditional animation didn’t seem to fit as well. Kenny doesn’t have any photos or videos of his past. And so it’s all kind of a sketchy memory and it seemed to really suit the film that we were doing.

We have to touch on your collaborations with Jerry Deaton and Stacey Stone. When did it all begin, and what distinguishes them as creatives?

Jerry Deaton has been working with us for four years. We found Jerry through being a finalist of a grant. So, we contacted Jerry. He’s got all the sound equipment and his own studio. It was a great thing. And, we decided we’d work with him. He has been a great cheerleader. He thought all the films that we did were important, relevant, and he was cheering us on. He does all the sound mixing, special effects and composition. He plays multiple instruments. Jerry is very talented. It’s a lot of fun going to his studio and working with him.

Jerry DeatonStacey Stone is my editor and director and I’ve always felt that she was the best person that I could ever collaborate with because she was absolutely the antithesis of what I am. And, you know, it worked very well. If it was black with her, it was white with me. So we took our time. We got to know how each of us works. Stacey’s technical ability to not only understand about different types of cameras and programs that she uses to edit and animate is remarkable. She would see something and she’d do it, or learn to do it and I thought that was great.

Diane & Stacey in StudioWhat is a contemporary social issue in the U.S. that you believe doesn’t receive enough attention in movies or the media?

One of the topics I think should be discussed is one about how children are exposed to smoking. I don’t think there’s enough that’s told about that and what happens later in life. Let’s let kids see what it looks like when you vape, you know, for six months. Let’s have ’em see what it looks like when you can’t talk or you’re sick in your 40’s, 50’s. And the other issue has to do with the rights to women of color having the same medical treatments as other women / women who are wealthy. I read a lot of stories about women who have been turned away from treatments and I would like people to know about what can be done, what kind of programs can be set up for people of color.

What is your next project? What can we look forward to from you and Pace Films?

I will tell you this, we’ve had some thoughts and have actually started filming a new project using our film about Kenny as a springboard to more films. We also have a book publishing company, Pace International Media and we hope to complete a compilation of short stories in the coming months.

KENNY

THE NONA