It is hard to imagine the pain a parent goes through after losing their child: Mountains of grief are met with unwelcomed acts of pity, and the weight of this tragedy is arguably the heaviest cross anyone is forced to bear.

Yet, Ashley Wren Collins captures this experience in her 17-minute short film I Only Miss You When I’m Breathing.

The film follows Nora and Warren, a grieving couple, who attempts to move forward after the passing of their young and only son.

The film opens on a shot of Nora (played by Lori Fischer, who also wrote the film’s screenplay), a middle-aged woman lying alone in her bed. Her eyes are wide awake, yet her demeanor proves that she is weary and exhausted by forces outside of herself.

As her phone rings on the table beside her, she remains motionless and unmoved. In a top-down shot, the camera pans along the length of her body in one fluid motion, captivating viewers with its direction and ease.

Upon completing its final ring, Nora opens her phone to listen to the voicemail message recorded moments before. The voice of a cheery neighbor emits from the phone’s speaker, cluing viewers in to the circumstance at hand: Nora has been absent for weeks from her normal social outings – but as as she locks the phone mid-message, audiences understand that this is for a reason, and she has no intention of going back.

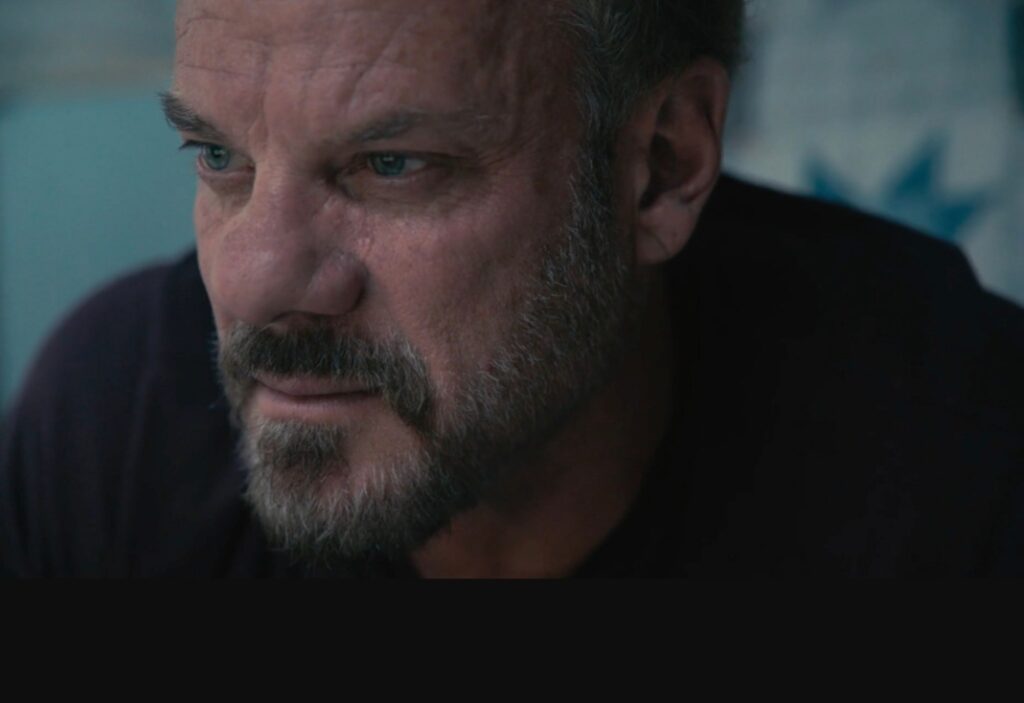

Shortly after, viewers are guided through a long and quiet scene that features Warren (played by country singer Phil Vassar), Nora’s husband, as he navigates his own silent and heartbreaking emotions. He rests for many moments in the driver’s seat of his parked car, and as feelings wrestle beneath the surface of his skin, it becomes painfully clear that his grief and turmoil are limiting his motivation and mobility – mentally and physically. Nora watches from inside the house as he remains motionless on his seat. After many moments of pause, Warren finally moves indoors to place the day’s newspaper on a stack of others that had been presumably gathered (and unopened) for months prior.

From here, viewers are guided through additional vignettes of the couple as they navigate their soul-crushing grief. The performances of Fischer and Vassar are earnest, raw, and unfiltered, providing viewers with a heartbreaking and accurate portrayal of what it feels like to experience the unthinkable.

The cinematography (P.J. Schenkel) is beautiful as well; many scenes are captured in emotional close ups with a color grading that reflects the state of each character, proving that an artistic eye was definitely at large throughout the film’s production.

While the acting and filming are both memorable within themselves, the rare addition of a musical score felt a bit out of place in the moments it appeared. The film’s soundscape was primarily filled with silence and tears, which was a tasteful decision given the gravity of the plot. Yet, there were a few strange placements of musical cues – surely, these were a testament to the story this film was inspired by (the real life story of Nashville country singer/songwriter Freddy Weller and his wife Pippy), yet it didn’t feel like a great fit for this film’s style and pace.

Even so, the moments of grief felt authentic and genuine, which is a testament to the abilities of the cast and crew to capture the realistic moments of loss, heartbreak, and crippling affliction.