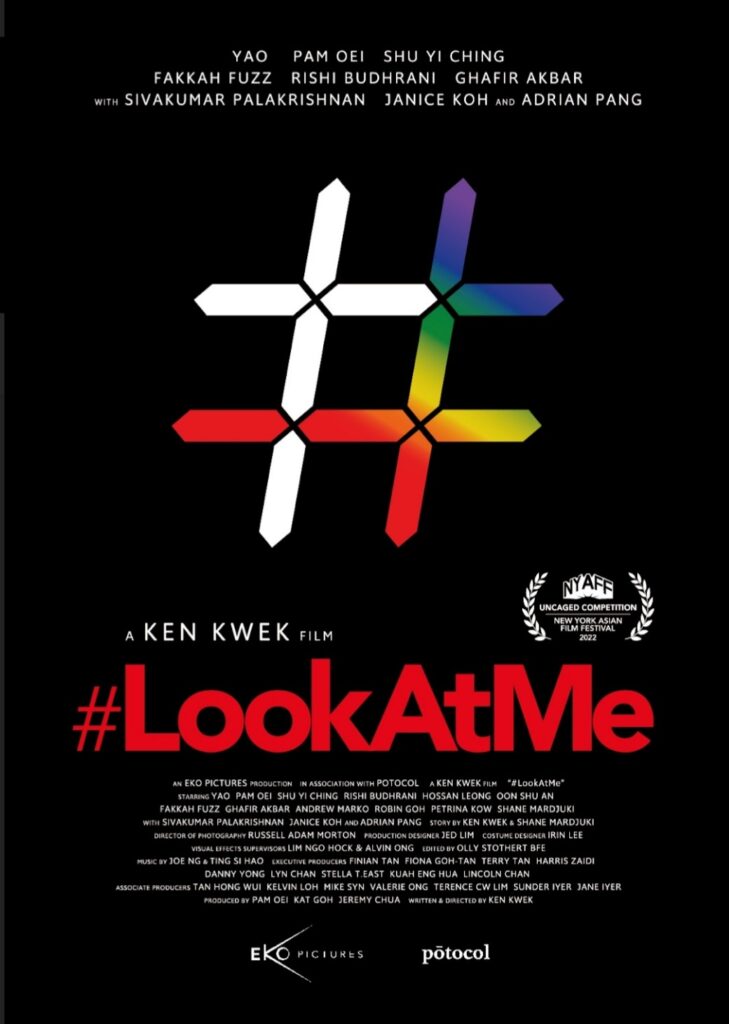

Take2IndieReview sits down with award-winning screenwriter, director and playwright Ken Kwek to discuss his second feature film #LookAtMe – a tragiccomedy about a family’s doomed fight for LGBTQ rights in modern Singapore.

Singapore is a Democratic Republic, and at the start of Ken Kwek’s #LookAtMe, the Asian nation certainly looks that way. But like any free nation, freedom is never completely guaranteed. In Singapore’s case, both freedom of speech and LGBTQ rights are under attack. An old, outdated law that criminalizes homosexuality (377A) has come into play and given power to anti-gay prejudice. Alongside, the limits on political speech and public assembly have curtailed LGBTQ activists from fighting back and together Kwek has taken actual events as basis for his film. In this, #LookAtMe gives us a tumultuous journey that tells us we must never stop fighting for our rights and what can happen if we take them for granted.

Where were you born and raised?

I am Singapore born and bred.

How did you begin your filmmaking career?

After graduating college in the UK I worked on a few movie sets as a camera assistant, including Britain’s first Dogme film, Gypo. Crew work was grueling but I earned my stripes. When I came back to Singapore I got a job as a journalist, but once you’ve caught the filmmaking bug it’s hard to shake it off. After three years in journalism I wrote my first screenplay, The Blue Mansion. That film went to Busan in 2009 and soon I was getting offers to write other scripts.

How did you arrive at a place where making socially relevant movies is your priority?

I don’t think that’s my priority per se. I think my priority is making entertaining movies. That my films happen to take on social themes is partly due to my exposure to different walks of life as a journalist. I still write for newspapers and magazines from time to time, to keep my ear on the ground and better understand how people live, especially those who are underdogs of society.

Singapore is classified as a Democratic Republic. But freedom is never perfect and anti-gay activism and speech are under attack. What does your film convey in terms of which fight is more important?

I don’t see queer dignity and civil liberties as distinct issues. I don’t see either ‘fight’ as more or less important, whether in real life or in the film. Both issues are inextricably linked in the wider culture, where to speak up about things that others consider taboo takes a bit of bravery and perhaps a bit of madness. Beyond LGBTQ rights, what I’m interested in is how free speech operates and devolves on the Internet.

The film is inspired by real events. Can you tell us if you met the subjects of those events, and how they were involved in developing the story?

I created fictional characters and a fictional plot without meeting any real life subjects. A few moments may echo real-life cases, but as a whole, the film is ultimately a work of imagination.

So much of this movie comes across as a country operating as a free society. That is until Sean unwittingly runs afoul of the powers that be. What is the movie saying about how all of us in so-called free societies are imperiled at any given moment?

The ideals behind free speech are important, but modern technology and social media has led to a coarsening of speech, because users are algorithmically encouraged to use more inflammatory language to get a bigger response. In #LookAtMe, both the liberal vlogger and the illiberal church leader know this instinctively. They speak crudely, because they know crudeness will get them maximum attention.

How did you go about researching what prison was like and then apply what you learned for the cast and crew?

I did interview several former inmates who had experienced time in prison. I wanted to replicate not only the physical dimension and details of the prison cell, but also to understand some of the behaviors of those who had to endure long periods of confinement and boredom.

Four men alone in a prison cell, how did you bring out the powerful performances for those isolating and oppressive scenes?

One aspect of the prison environment that I wanted to show is how inmates are deprived from books and reading. In one scene, the cover of a prisoner’s Archie comic has been half-torn off by guards, to censor words and pictures considered off-limits for prisoners. The lack of mental stimulation through reading or other meaningful activities creates boredom. And boredom feeds the prisoners’ worst thoughts and impulses. This is what I wanted the actors to convey in the prison scenes, and it didn’t hurt that we had a set built that was as small, humid and grimy as a real cell.

What does the film try to say about the unlimited power of any state to punish?

The film isn’t really about the unlimited power of the State. It’s about how fragile people are when they’re ignorant of how power works—not just State power but religious power, financial power, social media power.

Ricky’s boyfriend states his church isn’t like the pastor’s. Why was it important to show there’s also tolerance in society and religion?

Because such places of tolerance and inclusivity do exist – and no one should be excluded from the right to spiritual comfort.

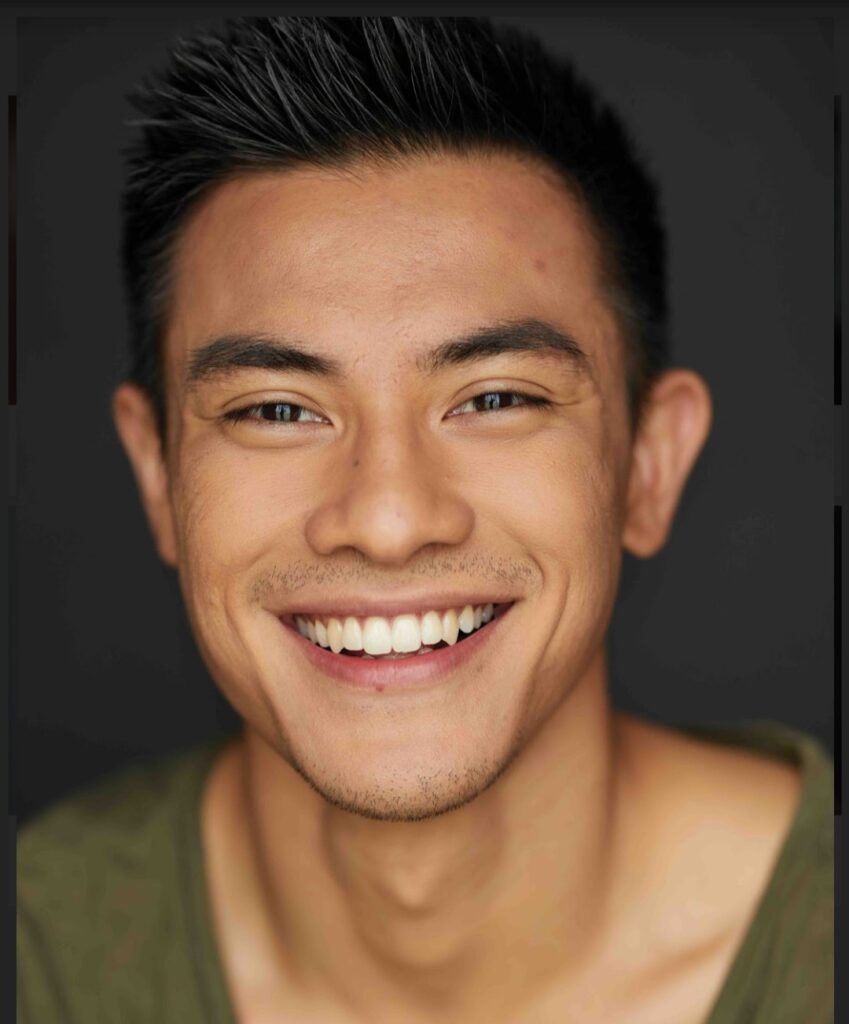

How did you help yao juggle playing both Sean and Ricky and then transform Sean from this carefree young man to a hardened prisoner/man?

I think a lot of what an actor does, the choices he or she makes, are their own. I may suggest possibilities, but ultimately I let the actor figure out how best to express those possibilities within the frame. I trust my actors. I wouldn’t have cast yao if I didn’t think he could play the twins in a convincing and powerful way. If I helped at all, it was in a practical way, by casting another fantastic actor, Shane Mardjuki, to perform both roles too, as yao’s body double.

To what degree is your film aimed at getting society to reconsider their beliefs in terms of the issues presented?

I don’t create films from a didactic perspective. I wouldn’t be able to make a good film if my starting point was “how can I change society’s beliefs?”. No, my aim is to create interesting characters and send them on a journey. My aim is to take the audience on a roller coaster ride. It’s about the thrill of movie-making, not about changing society’s beliefs.

This movie starts off very light, and even when Sean is arrested, the events remain relatively tame. So moving forward in the film, you could have continued in that tone. For instance, focusing on legal and popular pressure to free Sean. You obviously choose a much more dramatic course. Tell us about how the idea for the film evolved and settled on a story that practically tears the characters and the viewers apart at the seams?

When I wrote the first draft of the film in 2015, I saw it as something of a black comedy with satirical elements. But by the time we began production in 2019, the world had changed. Authoritarian leaders like Trump had been elected, the level of farce and violence in the political reality of the United States and the world meant that satire as a genre had lost some of its edge. How to ridicule ridiculousness effectively? How to make fun of reactionary violence or hate crimes effectively? The script had to evolve and I decided to take the risk of blending genres, so the film goes from comedy to drama to neo-noir thriller within the space of a hundred minutes.

Given the content and sentiment created by your film, how much did the process drain you?

This was a difficult project. It took seven years for the film to materialize from page to screen. We faced a lot of difficulty getting permissions and logistical support to shoot in many locations. But I was lucky to be backed by three outstanding producers and a group of investors who believed in me. They thought the story was compelling and believed in it too.

How has the film been received?

The premiere at New York Asian Film Festival went down really well. I think the audience really allowed itself to be carried by the journey of Sean, Ricky and Nancy Marzuki. They really got it, whooped and laughed at the fun parts but also gave due seriousness to the drama of the film. I love New York City and its people! It’s such a welcoming and encouraging place for artists and indie filmmakers.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a few new scripts, juggling a few different projects. I can’t go into details but certainly I’m looking to tell more stories that are Asian-centric and relevant to the American milieu.

www.kenkwek.com