Much of piecing together history is the examination of letters. After all, ancient heads of state and business colleagues didn’t have email or tape recorded phone calls. So if the correspondence still exists, we have important accounts of why WWI started or how so many light bulbs appeared over Thomas Edison’s head. Of course, unabridged insights are more likely to be found when George Washington wrote home to Martha. That said, there is a huge omission in the historical record. Letters between gay lovers were often burned for fear of discovery, and WWII England was no exception. Fortunately, one brave couple took the risk, and their letters becoming public in 2017, Andy Vallentine’s Oscar-qualifying short has magically brought their story to life in The Letter Men.

Under the skies of England’s overcast glum, Gilbert (Garrett Clayton) and Gordon (Matthew Postlethwaite) first meet on a sail ship and illuminate the stereotypical haze with a storybook spark. Catching each other’s eye, Her Majesty certainly wouldn’t have approved. But the chemistry the actors emote in their affectionate glares and connective dialogue definitely steals The Crown Jewels.

Not even the prim Victorian mores that linger onshore can put a damper on a journey that seems to have pretty strong sea legs. Hitler, on the other hand, is a whole other ball game, and when the incoming Battle of Britain appears overhead, partly cloudy becomes a category five hurricane.

The screen goes black and a year later we find Gordon in seclusion. In his study, the atypically British sunlight that emerges from the window is trying to provide a beacon. But, unfortunately, with the clouds of war and the uncertainty of Gilbert’s service, the darkness has the upper hand.

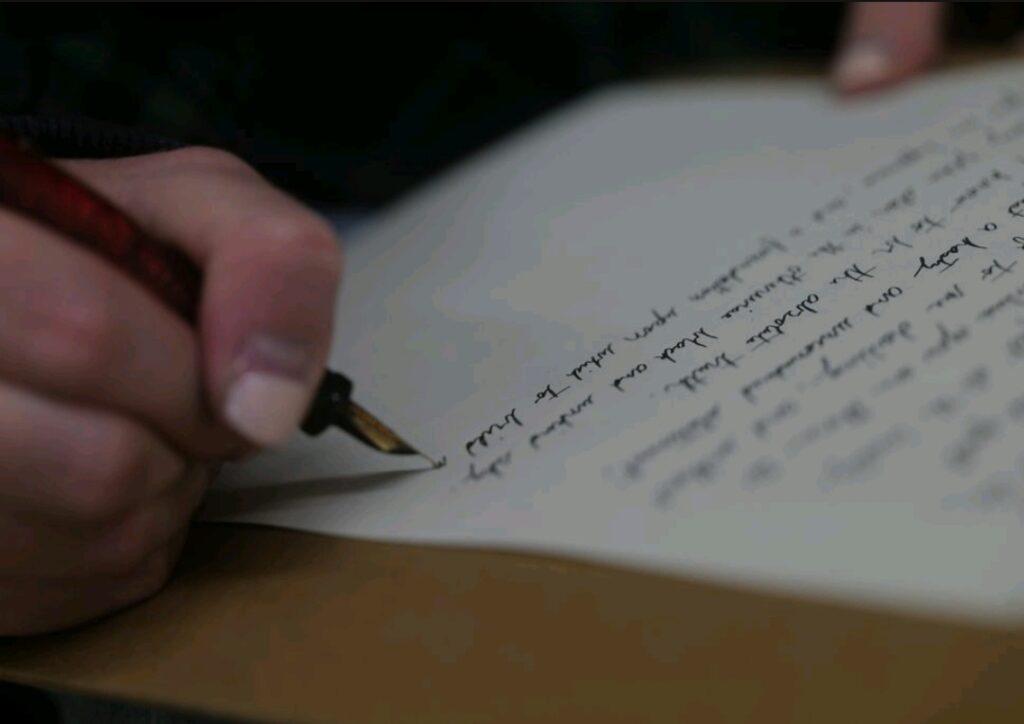

Alongside, the enemy that the isolated lover must face is revealed through the distinct play of incidental noise. The click of Gordon’s pen, the rustling of paper and the scoff of his shoes highlights how alone he is, and adding the melancholy melody only accentuates the solitude.

Postlethwaite’s features show the weight, and there’s little facial resemblance to the carefree roll of summer’s tide. The glide of his pen doesn’t do his contours any favors either. The expected release of self-expression not forthcoming, the actor’s grimaces convey the dichotomy of what is and what should be.

At the same time, the light and the dark of the Oren Soffer cinematography are still competing, and we feel the double edge of Gordon’s mixed emotions as he signs, seals and delivers.

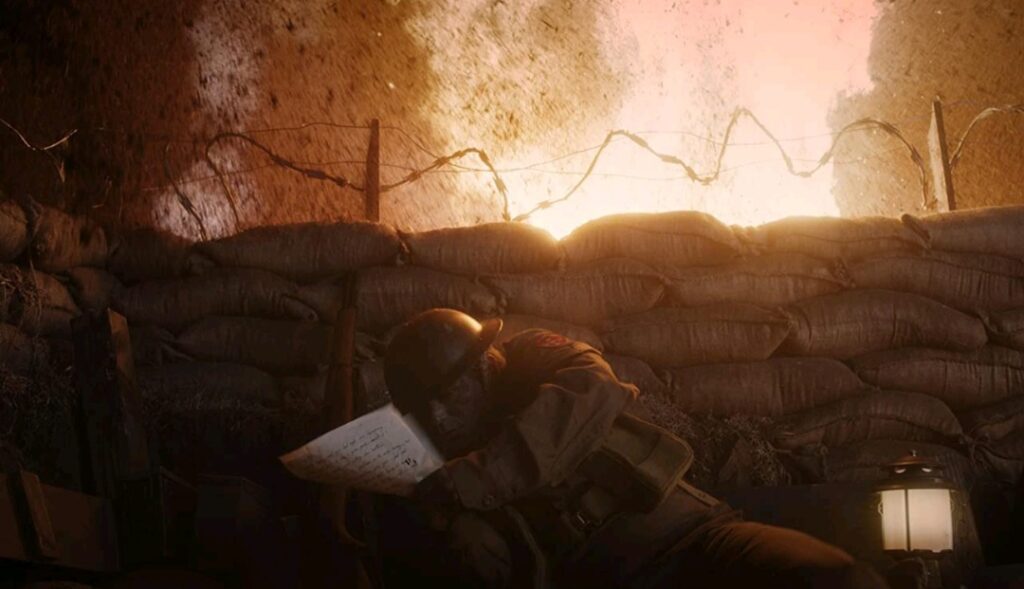

The letter receding into the darkness of the mailbox, it emerges under the same purview in Gilbert’s foxhole. There, the diminishing light has far less prospects.

A flickering gaslight in this case, the occupants have no choice but to hang on to the dim illumination. It’s the closest thing they have to hope. The light shining brightest on Gilbert, we get more than just the romantic power of Gordon’s words in voiceover.

The sound delivery by Nico Pierce again sets the stage. The terror of the war isn’t conveyed by the bursting light of falling bombs or flailing bodies, but through the off screen reverberation of machine gun fire, troop movement and air power. As a result, the danger becomes all the more real since death usually comes unseen and out of nowhere.

Thus, there’s an ever-present necessity to hang on every word of Gordon’s letter, because we may never hear the end of the next sentence. In turn, Clayton does his part as an intent listener, and without a line, he expresses the wide range of emotions that the situation and the film demands. So the moment defined, the need for denial is paramount, and flashbacks take us along like the lifeline they are.

The light and the color live here, and while there’s darkness, it doesn’t really compete. Instead, the silhouettes essentially make the couple seem as though they are the only two in the world that matter.

Of course, memories can only provide limited protection from real life. So the visible spectrum shifts back, and the decimal level returns. Gilbert and Gordon are separated again, and we are overcome with heartbreak. But there’s also togetherness, and no particular audience is intended. Uplifting and inclusive, these letter men want us to know that love, after all, is universal.