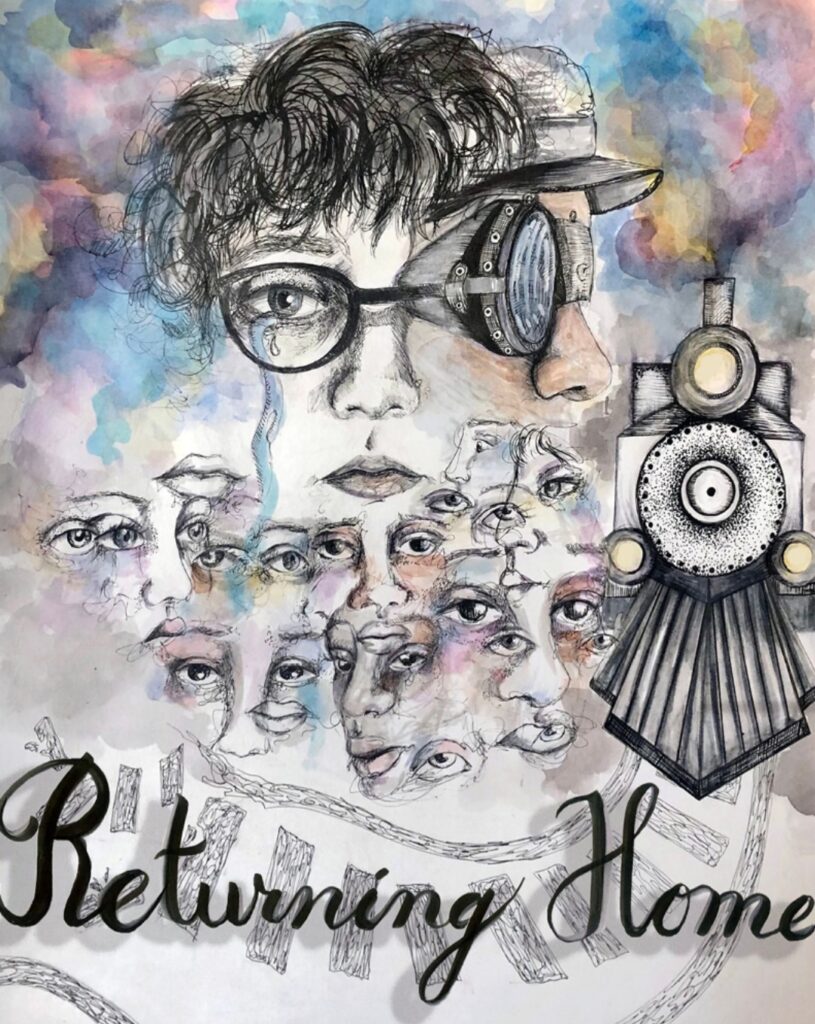

Returning Home, directed by Jamie Lazan, is an existential collage; a cross-stitch of young adult fears and anxieties. The film, made by The Human Arts Collective, is a mid-length series of interspersing vignettes. It is low-budget, filmed remotely across multiple locations, with some footage appearing to be captured by the actors themselves. Despite this, the film carries a weight that is more than the sum of its parts. The quality is inconsistent, but at its best moments, it is surprisingly captivating. It is certainly raw, the fundamentals aren’t always executed to a high level, but there is something endearing and relatable about the film.

The film opens with footage of train tracks. The camera flies over the tracks, initiating what seems like an endless state of motion. A voice-over muses about being lost in living, drowning in melancholy memories and the eternity of forever. Cutting to a room, we are introduced to a young man, Nickel (Nick Freedson)—his hands covering his face in a sign of resignation. He describes his desperate situation, cycling through a series of metaphors. As he does so, more people appear on screen: Apollonia (Mary Kate Magee), Suli (Nneka Damali) and Lucinda (Kayci Rose). That they are introduced in this way, in synchronization with Nickel’s words and movements, implies that they are internal states of one and the same person—à la Pixar’s Inside Out. They seem to be voices in his head: the rumbling echo of his brain. As a result, the film is best framed as an odyssey through one man’s splitting mind (the film literally using split screen at times); or an exploration of the different metaphors of emptiness, loneliness and isolation.

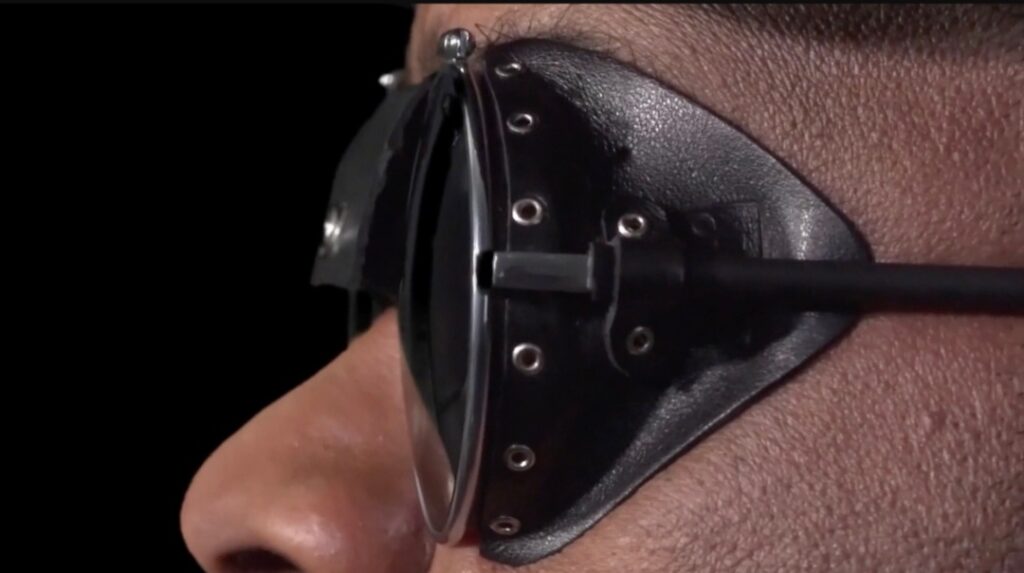

Whatever your conclusion on the form of the film, the content is clear: existential angst. Questions instantly arise. What connects the situations? Where is the train going? Why are they on the train? How do they get out? The Conductor (S. Todd Townsend) is our imperfect and enigmatic guide. Wearing a peaked hat and round dark sunglasses, he is framed in close-ups and other shots isolating his body parts. He can conduct but he can’t instruct, so he says. The Conductor has a certain omniscience, almost like Morpheus from The Matrix, and appears to be able to communicate with Nickel, Apollonia, Suli and Lucinda as they deal with their individual situations, though they can’t see him. Is he benevolent? It’s a little hard to tell. His intentions aren’t clear, though his tone is warm and encouraging.

The title, Returning Home, provides some direction. This is a journey of self-discovery or re-emergence of sorts. We are shown different examples of the ways people seal themselves off from the world, or are simply trapped by it: someone hardened by bullying to become a bully herself; someone adept at building walls in relationships; two others trapped in a swimming pool and a burning house respectively. The film encourages the split protagonists to exchange their fear for intuition, to listen deep within so that they might escape. There isn’t much more explanation than this. Doubles of the protagonists appear later in the film, communicating with them and confusing the rules of the film even further. The film is not fatally incoherent, but it does lack clarity at different points.

One of the strengths of the film is its use of disconcerting abstract situations—a deep pool of water, an open forest area, a burning house—to convey the depths of a person’s dysfunctional mental state. The different settings are well-chosen and flesh out the feelings that the opening monologue sets in motion effectively. Though the metaphors are not necessarily breaking new ground, they are common enough in film and literature, the fragile (often tremoring) voice-overs do add a layer of genuineness to the visual representations. An electronic synth score underlays the neuroticism shown on screen, helping to construct the dreamscapes and the constant feeling of movement.

The swimming pool and the burning house are the strongest of the situations. The former with its impressive establishing falling shot, low-budget underwater camera work and strangely arresting poetry, the latter with its suffocating atmosphere and alarmed minimal performance. Freedson and particularly Damali deliver performances that impress feelings of insecurity and unease. Both actors rely on facial acting and mirrors, as the technical limitations mean they are rarely framed full-body. The other two situations—the open forest area and the zombie comic—don’t hit the same levels. The acting is of lower quality and feels more stilted, performative and aware of the camera. The underlying meaning of both of these sections also doesn’t feel as incisive or lasting.

Returning Home is an adequate, if limited, take on the existentialism of young adults in the 21st Century. The film surprises in its ability to create genuine emotion, especially given its technical and visual simplicity. The film is uneven in its execution, shifting from situation to situation, but the good moments outweigh the bad. The poetry drives and maintains the speed of the story, providing interesting enough language to interpret the events taking place on screen.