Science fiction exists to make us imagine – and spaceships, robots, aliens and parallel universes are never far from view. On the other hand, the best futuristic tales don’t arrive at the other end of a worm home and claim that the human condition can only be explored by a far flung journey. Star Trek, Dune and Foundation are among the great works that – in truth – stay close and are meant to make sense of the world we live in now. Almost Home by Nils Keller can be added to the list, because while there’s no place like home, this 30 minute short film shortlisted for an Oscar, reminds us of something even more basic. Home is nice, but who’s there, is what matters most.

So in keeping, it makes sense that the film begins with the sounds of Earthbound nature, and along with a laid back little Indie strum, the commensurate images follow. A couple of teenagers in the throws of an innocent romance join the landscape and assure that the human touch will always reign over the technological leaps of any age.

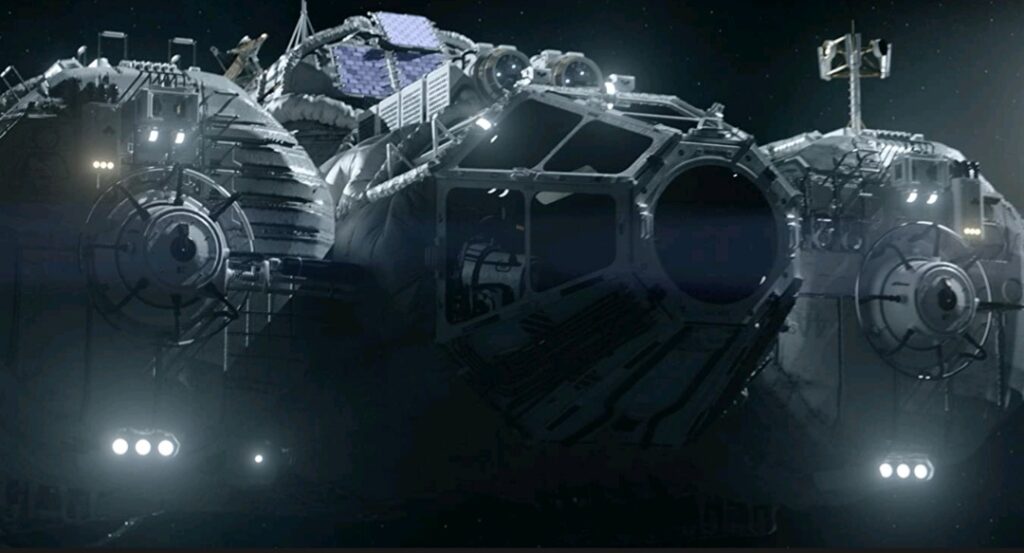

Of course we must lift-off, and a small orbital space station is the setting. Sophisticated by our standards, this nearby future doesn’t seem to have breached faster-than-light travel and established a United Federation of Planets.

Nothing so galactic, the stratosphere still makes electronic communication a home to teenagers and adults alike. Age doesn’t discriminate when it comes to the desire for the real thing, though. In this case, Jakob (Jeremias Meyer) knows he’d rather be on Earth with Lisa (Malaya Stern Takeda).

No such luck, no one can hear you scream in space, and the same goes for pining. Leaving his quarters, Jakob floats through the space station, and vomit comet or not, the masterful zero gravity effect and realistic Linda Sollacher set design brings home the loneliness of space. The soulless hum of the station and the incidental personal contact with the interior, only elevates the solitude. So his sojourn through the quiet maze has him come off more a ghost than an astronaut.

And then it gets worse – Jakob lives with his mom (Susanne Wolff). Well, she’s actually pretty cool, and Wolff’s portrayal is in the stars and down-to-earth at the same time.

In other words, Mom has both the resolve of our favorite starship captains and the playful nurture of a mother knowing best. In turn, Meyer’s play off his co-star takes solace in Wolff’s ability to multitask, and together, the characters show us a bond that cuts through the loneliness.

Even so, the duo isn’t just above the cloud to stargaze. Jakob has an autoimmune disease that previously bound him to a wheelchair on Earth. The trip into space has provided a treatment, and while he’s still unsteady on crutches, life on planet Earth is about to take a giant leap.

Not so fast, a virus has emerged on Earth, and the prospects of another global pandemic looms. Yes, the future is now, and as we know, the science remains elusive. So again, when competing schools of health policy emerge and politics are added in, individuals are left to pick sides.

Jakob’s choice is then complicated by his condition. Possibly more susceptible to the disease, he doesn’t have to tune into social media to sort out the varying agendas. Neatly encased, Mom and the expertly crafted Lukas Väth hologram of Dad (Stephan Kampwirth), represent the opposing points of view.

In this, Kampwirth gives a mix of emotion and everyday pragmatism that provides a powerful counter to the scientific second nature of Mom. The parents are also both smart enough to understand that they could be wrong, and along with the whole drama being put on the clock, the shared doubt really elevates the stakes.

Jakob is also a teenager and his terrestrial girlfriend is waiting. Meyer’s easy shift from youthful exuberance to a cold impetuous adolescent rage, kicks the drama up even further. All rushing toward a vortex, the hum of the engines gets louder and the strained sound has the viewer feeling like a blackhole is going to get us either way.

But the story is still here. Like us, the pandemic we have lived through has not lent itself to a specific right path and is highly individualized. Mostly window dressing, though, the uncertainty this film explores has nothing to do with microbes or six foot comfort zones.

Jakob is 17, and that leaves him and his parents at a familiar precipice. Is he old enough to make his own decisions or do his parents still reserve the right? We could bang the climatic drums like in 2001 but there’s no need. The dramatic conundrum is as old as the stars, and with the right people in your corner, Almost Home reasserts that we don’t have to go there. . . to find an answer.