Take2IndieReview sits down with Director Alfred Pek to discuss his documentary film Freedom Street.

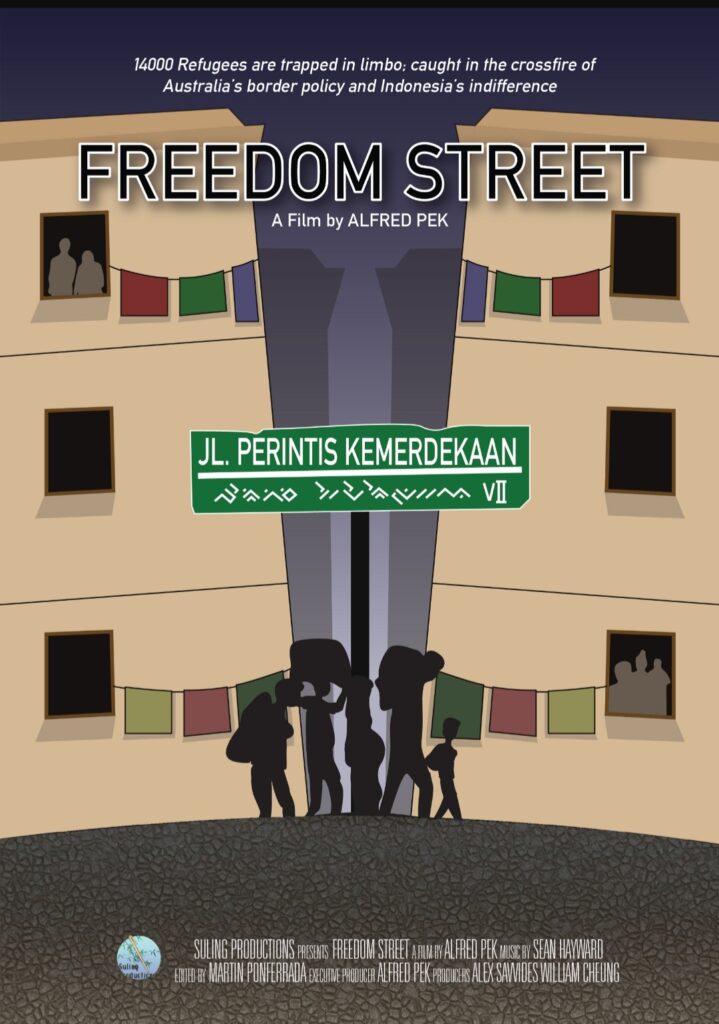

People fleeing their homeland from war and oppression is nothing new. So the modern world has attempted to deal with the problem in legal terms. In 1954 and 1967 numerous countries signed refugee treaties to give official status to the disenfranchised. Even so, nations continue to find a way to skirt their obligations, and Australia has really taken the omission to an unprecedented level. Instead of letting refugees into their country to await a hearing, they house thousands of people in offshore detention centres in Indonesia. Out of sight and out of mind, these stateless people end up with a heartless form of indefinite detention and Alfred Pek hopes his documentary film Freedom Street can force change by raising the profile of the atrocity.

In your hope to empower the disenfranchised, how did filmmaking grab your attention as a vehicle for change?

Filmmaking has always been the most accessible form of communication throughout all ages as it carries through our very instinctual oral tradition. As impactful the literary works are for a lot of people, the audio-visual medium has never failed to captivate the most attention and reach. Personally as well, I feel there’s so much more story dimension that can be conveyed in the most compact way when this medium is done right.

In your early career, what was it like to see people moved by your work and how did it inspire you to want to do more?

It is really one of the biggest validations for my personal and professional stance. There is no better feeling than having been rewarded for the hard work and effort you have put in. Especially when you have set the intention to what you envisioned. And I hope that this is the beginning for more exciting (and the daunting) things to come as I endeavour to pursue a much more personal, but socially bigger cause.

In America and around the world, we often see Australia as this big gregarious and welcoming nation. How important was it to show a more balanced view?

I personally would encourage people to proactively explore the worlds beyond their own, this is imperative towards a more balanced view of the world. Living in today’s day and age, especially coming from a rich country with a history of colonisation and immigration, it’s finally the time for all the countries within the context to come to terms about their origin story. This requires a real strength and courage to not only research and learn about these facts, but also the dedication to commit in working towards uncovering what is needed. Time and time again, we all need a reminder that there’s many people that not only have been silenced and underrepresented, but often invisible and are currently suffering at the hands of unnecessary cruelty of politics.

What was the spark that led you to do this film and why the title Freedom Street?

The street sign that is displayed in the film and the promotional pictures, when translated to English, is called ‘Pioneer of Freedom/Independence Street IV’. This particular street sign is the very street where a lot of these refugee accommodations, in the city of Makassar, Indonesia, are located. This was, perhaps, the biggest contextual irony that neither the local Indonesians, nor the refugees, nor the international journalists are aware of. It had become the biggest omen for me to take an action in telling this very invisible, yet important story, in our region.

What were your biggest obstacles in making the film?

From the moment of conception until completion, this film was plagued with obstacles. The topic itself was barely on anyone’s consciousness and it’s not exactly a light matter. The refugee advocacy movement in Australia is already busy and under constant pressure to fight for the rights of those who are directly affected by our harsh border policies. What we’re talking about in the film, whilst connecting all the dots, it didn’t register the significance to these people until they literally watched this film. And due to the lack of popularity, it was very difficult to attract crew, funding, as well as the dedicated people to collaborate with to help with the film’s development. But by far the biggest obstacle is how much the personal relationships with the film stars was developed throughout the film and how much shock and personal involvement I have had in order for myself to help better the situation for these people.

Putting detention off shore could possibly be seen as a way to give the refugee issue a lower profile in Australia. How effective has the policy been achieving that goal?

It has been very effective as the situation is quite literally out of sight and out of mind for most of the general public. Combined with the outsourcing and the privatisation of the management of offshore detention centres, this creates a perfect recipe for rendering the matter almost invisible, except for the bravest and most diligent souls of those who are uncovering this atrocity.

What is at stake for the government of Indonesia and what is the Indonesian public opinion on the issue?

There is no stake per se for the Indonesian government to manage these refugees, and it barely registers any consciousness to the Indonesian public. The refugee population in Indonesia is far too small to make a dent of any major news in the country. There are simply far bigger concerns and local populations affected domestically for their own issues. The only reason Indonesia actually cared about this issue is because of Australia’s funding to incentivise the warehousing of keeping these refugees. And it goes without saying that there’s some lucrative interests for the few that benefit from such arrangements.

What pushback have you gotten from the Australian government and what response did you get in attempts to interview someone?

My interview requests for anyone who works for the Australian government, relevant NGOs like UNHCR and IOM have been ignored. They simply do not acknowledge our request or decline them at best. The pushback has also been from finding the film stars – as sharing their stories would have raised some security concerns over their resettlement chances, and some of the experts interviewed were simply too busy and unavailable.

What is involved in entering the detention centres, and how dangerous was it to be a filmmaker exposing the story?

Thankfully, I did not have to enter most detention centres. I was able to source most of the filming from internal residents who recorded it. The two times I was able to enter the community housing was because I was smuggled into the centre. This was because my friend and film star lied about my identity and my purpose of being there. For some reason, my looks also blend very well with the refugee population there, strangely enough. There were a perfect set of circumstances that led me to be in a position where I was in a relatively safe position. I don’t think this will ever happen again to any other people.

Where does Australian public opinion stand and how do you hope your film has an impact?

Since this is something that’s barely in the Australian public consciousness, there’s nothing we could really gauge, but we hope that the advocates and changemakers who have seen this film will be the main drivers to raise the issue to the public. This film’s intended purpose is to become a useful and convenient advocacy tool that these people will need to fully contextualise this entire situation and bring about change.

How have other countries with refugee issues picked up on Australia’s detainee strategy and taken strides to implement the same type of offshore detention policy?

The US and Denmark have essentially a very similar system to Australia in which asylum seekers are detained to be “assessed” onshore. However, no other country has followed Australia’s footsteps when it comes to assessing asylum seekers in Offshore detentions. Furthermore, no country in the world other than Australia (and subsequently influencing Indonesia) has indefinitely kept detaining people after they are recognised as refugees in immigration detention prisons. Most countries, once they recognise these people as refugees, allow them to live in the community/refugee camp awaiting permanent protection visa or fully resettle these refugees to a third country that will accept them. Australia for the longest time kept detaining refugees in offshore and onshore detentions as a political pawn due to the fact that these people entered or attempted to enter Australia by boat rather than by plane.

How did you decide on the three subjects?

I was searching for people outside of the known major centre of refugee population across the archipelago. This led me to choose the city of Makassar in Indonesia which has a sizable refugee population. I did a referral call out to the people who would be interested in sharing their journey. I insisted on at least one female subject. The people that ended up agreeing to be on the three subjects were simply the bravest people out of the bunch. There were no more other subjects that were brave enough due to the perceived risk of jeopardising third country resettlement opportunities for those individuals if they were to tell their stories

What is it like when you enter, greet your subjects and then leave them behind?

There’s no justification with how I feel about this. The best description on how I would feel going through the experience when I enter, greet my subjects and leave them behind feels like I entered some sort of alternate reality and fever dream. It felt like an intense surreal journey, partly because of the disbelief where everything was taking place (being in my original home country). Furthermore, there’s no best way to describe the overwhelming sense of existential crisis I endured realising the disconnect that something like this could be perpetrated by not just one, but two of my home country. Furthermore, it’s not even registered by almost everyone from anywhere around the region despite the importance of the context this film brings to this issue.

If detention awaits a hearing, how does it end up being indefinite?

It ends up indefinite because resettlement entirely depends on the resettlement country’s willingness to choose the region in which they resettle refugees from. Since Indonesia absolutely has no commitment to resettle these people locally, and Australia blocked refugees who arrived in Indonesia after March 2014, these people simply end up in an indefinite stallment, going nowhere and no option to come back home if they were stateless.

What is media coverage of this story in Australia and Indonesia?

The topic coverage is minimal, there are a few articles mentioned here and there. There is certainly slightly more coverage from the Australian side that I was able to gather for research, however this was only covered by the more left leaning media in Australia or in the case of Indonesia, either this made it as a very localised news or an English (international/expat readership) publication. Sadly, nothing out of this ever went viral or received any massive coverage anywhere else.

How are international bodies addressing this issue?

UNHCR doesn’t have any power for resettlement, they are simply a vetting body that registers refugees around the world including those who are stuck in Indonesia. IOM manages the detention centres and the management of the daily lives of refugees. None of these organisations address the fundamental issue of safe resettlement pathways, nor actively prevent any act of wars or crisis that lead to this mass diaspora of people in the region. The absolute state of this issue has simply been abandoned by major politics of any resettlement countries. There is no easy solution for this, but when there’s political will there’s a way. The best recent example of this would be the latest Ukrainian Refugee Crisis and how a lot of countries were willing to quickly resettle these people as compared to other people from around the world.

How can people around the world help?

To our specific context in our region, regarding the act warehousing of refugees around Australia’s neighbouring country, there has to be more political pressure domestically and internationally for Australia to change this policy, and instead cooperate with its neighbouring country to create a safe passage for refugees who are seeking refuge in our region. This domestic issue has gone international and thousands of people’s lives are at stake – especially those who literally have no home at all in the first place.